(Click the above 'LKFF News' and 'LKFF Interviews' links to access the other pages of this site subsection dedicated to the 2018 London Korean Film Festival)

LKFF2019 REVIEWS:

*All other reviews can be found in the main 'Reviews (Korean Films)' section of this website - see the link at the base of the Hangul Celluloid banner above*

LKFF2019 Review #5:

|

"Stop coming here! You have no right to be here. What did you do while everything happened?

You call yourself a dad? You tried to carry Ye-sol into the sea? She can't even get into the bathtub!

You're no dad!..."

Synopsis:

Jung-il (Sol Kyung-gu) returns to Korea after a prolonged period working abroad to not only find his wife, Soon-nam (Jeon Do-yeon), avoiding him and virtually refusing to see or indeed talk to him but also discover she has had divorce papers drawn up which she’s ready to file. Unwelcome in his own home, he instead stays with his sister nearby, enlisting her help to try to reconnect with his young daughter, Ye-sol (Kim Bo-min), much to Soon-nam's largely unspoken exasperation.

For, she refuses to forgive Jung-il for being overseas when their son, Su-ho (Yoon Chang-young), was killed in the Sewol ferry disaster, at least in part holding him responsible for his death as the boy was travelling to visit his father when the tragedy happened and she has no interest whatsoever in talking about her feelings of blame, guilt and indeed despair with anyone, let alone him.

However, with friends, neighbours and a victim support group planning a memorial/remembrance get-together for what would have been Su-ho's next birthday – against Soon-nam’s express wishes – those feelings begin to bubble towards the surface looking increasingly likely to be finally and vehemently vocalised for any and all to hear...

Review:

Melodrama has long been a mainstay of Korean cinema since the years and decades when extreme censorship came down hard on any narrative critiquing politics, criticising the Korean Government, featuring overt sexuality, depicting alternative lifestyles deemed as inherently immoral, and the like – specific taboo subject matters being at least partly dependent on the regime in power at any particular time. The feeling that melodrama by its very nature was one of the few genres relatively safe from censor scissors or outright banning (or at least as safe as any genre could be) pervaded and entered the Korean cinema zeitgeist, if you will, to the extent it still holds true in today’s more liberal times, certainly for fans of classic Korean films at the very least. As such, the fact that Birthday is unashamed in ultimately showing itself to a melodrama of the highest order (and in this case that is a strength) while detailing a story based around a true life tragedy that garnered severe criticism of political and governmental action, or inaction, and brought protests beyond what would normally be deemed public outcry may on the surface seem to be somewhat of a dichotomy. However, while there are passing references to the ferry disaster of a political or societal bent (different attitudes to and arguments over victim compensation; soap box calls for petition signatures aimed at forcing the Government to make greater efforts to find victim bodies still missing and raise the ferry from the murky depths) these are elements of the story only rather than being at its core.

For Birthday is far more an intimate, personal dissection of the soul-wrenching pain and paralysing psychological scars that tragic and unnecessary loss brings to those still living and (from their perspective) left behind - be they family, friends or even simply disaster survivors - with emotionality, catharsis and ultimately healing as its raisons d'être and as such Birthday not only fits into melodrama like a proverbial hand in glove but also absolutely sets that genre as the one and only that could adequately and effectively serve the narrative's thematics, both powerfully and tear-inducingly so.

|

Su-ho's death has turned his parents’ physical separation into a gaping emotional rift and Soon-nam especially has internalised her grief taking it to her very core, choosing to suffer alone and in keeping Jung-il beyond arms length pushing him to do the same. Humans by their very nature can lapse all too easily into selfishness, thoughtless and even seemingly uncaring action when in a solitary bubble of problems and/or grief and Birthday gives repeated implications of just that for both Soon-nam and Jung-il.

For example: Soon-nam has continued to buy clothing for Su-ho since his death and on bringing home a new coat to hang on his bedroom wall she excitedly shows it to her young daughter who straight away looks into the bag it came in to see what’s been bought for her, only to find the bag empty; or consider Jung-il accompanying little Ye-sol on a school trip to the beach where, when she refuses to enter the sea on being beckoned by a teacher, he picks her up and starts to carry her in, not having even taken the time to find out that her brother’s drowning has made her so scared of water that she won’t even get into a bathtub.

Not only that, but while Soon-nam’s decision not to share her pain with those around her is in an effort to even carry on from day to day, it too is steeped in self-destructive selfishness (even if she doesn’t realise it herself) for in not doing so her belief that no-one understands what she’s going through is left unchallenged, leaving her closed to even the possibility (and indeed fact) that others are in as legitimate pain because of Su-ho’s death in spite of their bond to the dead boy not being as close as familial. That in a way could be said to be somewhat disrespectful to Su-ho and his importance to those he was close to in life, especially when his importance to his mother (the other side of the same coin) is absolutely everything to her.

The deeply moving and poignant conclusion to the film’s narrative (all set in a single room) runs with this idea, extending it to resolutely state that only by embracing the pain of others and sharing her own can Soon-nam have any chance of healing, in the process not only paying suitable respect to the memory of her son but also being heartened and lifted by an understanding of the respect he earned in life from those around him.

That is an ultimate mission statement as worthy as any, Su-ho’s life from the perspective of those he touched standing as a fitting tribute to each and every one of the tragic victims of the Sewol ferry disaster.

|

The specifics of the disaster are touched on only briefly (mainly through dialogue from a young woman who survived). As far as I’m concerned, that is a wise move on the part of director Lee Jung-un firstly because emotion is far more important to Birthday than facts and figures and sidestepping them ensures there’s nothing to interrupt the narrative flow and secondly there has been so much coverage of the event itself across a plethora of media platforms that there’s not a single Korean, I reckon, who isn’t wholly familiar with the intricacies of the tragedy, so in a personal and human based story further overview detailing simply isn’t necessary. For international viewers, even vague knowledge of the ferry disaster is enough to get everything the director intended from the film and even those with no knowledge of Sewol whatsoever will get sufficient information from the narrative to do the same.

Birthday’s pace is meticulously measured, building gently to allow every narrative nuance adequate time to really count in terms of audience immersion. Add to that the fact that layers of Soon-nam’s psyche are gradually unveiled going deeper into the mindset of a female in excruciating emotional pain and I for one was reminded of the work of director Lee Chang-dong on more than one occasion, both generally and specifically (one scene in particular almost cannot fail to bring Lee Chang-dong’s Secret Sunshine to the minds of Korean film fans). Lee Chang-dong was in fact Birthday’s producer so I assume he too felt an empathy to the narrative and Lee Jong-un's directorial style (she previously worked in the directing department on Lee Chang-dong’s Poetry). Considering the fact that Birthday is Lee Jong-un's debut feature, all of the above really can be taken as quite an accolade and certainly raises my anticipation for her ongoing career and excitement for her next project.

Summary:

Unashamedly a tear-inducing melodrama, Birthday is a powerful film that ultimately stands as a tribute to each and every one of the innocent victims of the tragic Sewol ferry disaster and indeed those left in abject despair by their loss.

BIRTHDAY (생일) / 2019

Director: Lee Jong-un

Starring: Jeon Do-yeon, Sol Kyung-gu, Kim Bo-min

|

All images © Next Entertainment World

Review © Paul Quinn

|

| |

|

LKFF2019 Review #4:

|

"How can you just leave for work like that when your husband is so sick? So, your work is more important than your husband, is it?

I don’t know about your family, but we are not so poor that we need you to bring in money.

Once a woman gets married, it’s her duty to serve her husband..."

Synopsis:

Despite her mother's repeated protestations that she should find a man, get married and settle down to a life as a housewife, Jin-suk continues to study virtually night and day for an exam which would qualify her as a judge. Not long after passing the exam and beginning her new career, Jin-suk catches the eye of construction company boss Mr Kwon who, both impressed with her fairly lofty professional position and quite taken with her effervescent beauty, soon becomes obsessed with seeing her married to his son, Gyu-sik. When Jin-suk’s current would-be relationship disintegrates as a result of the man in question demanding that she give up her dream of a professional career (something she would not for a single second consider), she finally begins to date Gyu-sik and the two are indeed eventually wed.

However, as Jin-suk tries to find a balance between her new home responsibilities and her all-important work, jealousies from both her (new) immediate and extended family start to emerge; jealousies that could ultimately put her very life in mortal danger...

Review:

Thematically and indeed in terms of narrative focus, A Woman Judge can almost be considered as consisting of two parts; one morphing into the other at pretty much the film's halfway point.

The first of these is wholly centred on Jin-suk’s rather insecure position within her husband's family as she tries to balance judicial responsibilities and familial demands; others' (vastly differing and often negative) attitudes to her fairly lofty professional position; and the repeated efforts of some to wholly derail both her work aspirations and her attempts to fit in as best she can with the traditional notion of a woman's requirement of providing for the needs of her husband first and foremost and, to almost as great an extent, the demands of her mother-in-law (or more accurately her step-mother-in-law).

From the very outset of A Woman Judge, director Hong Eun-won deftly compares the virtual polar opposite attitudes towards Jin-suk from those around her – male vs. female; young vs. old – and it is here that A Woman Judge both shows it's strength and brings some surprises:

The wholly supporting attitudes of males of middle age (namely Jin-suk’s father and father-in-law) towards her professional efforts stand in stark contrast to those of her mother and step-mother-in-law who both feel she should abandon her career and take her place servicing the needs of her husband, as they feel should be the case for all women of the time. While this in itself is thematically insightful, what is all the more engagingly surprising is the fact that the younger people around her – her husband, her sister-in-law; her ex-boyfriend etc.) have attitudes as equally as traditionally conservative and close-minded as the middle-aged matriarchal family members. However, what stands out most of all is the fact that almost every woman Jin-suk comes into contact with stands in opposition to her life choices, and even those females outwardly showing support are largely only doing so to cover their backstabbing or because they think they can somehow benefit from Jin-suk's professional power, rather than truly believing that a woman has a rightful place in professional society. In fact, even when Jin-suk’s husband is found to be cheating on her with a female work colleague, the general attitude of gossiping female family and associates is that Jin-suk must simply have driven him to it by failing in her marital duties to him because of her (unnecessary) job. Whether this wholly disparaging standpoint is a result of the traditional ideals drummed into women of the time from early youth to adulthood; jealously stemming from Jin-suk succeeding where they simply couldn't; or a combination of the two is never definitely stated but the question does beautifully give pause for thought and further allows A Woman Judge to linger in the mind long after the credits role.

This first part/half of A Woman Judge also has some understatedly humorous moments that while lightening the load somewhat still speak of societal issues, historically. For example, we see Jin-suk adjudicate a law case of male against female in which the woman in question states that she only slept with the man because she thought they would be eventually married, to which Jin-suk asks “So, did you also assume you were going to marry all the other men you've slept with before this?”, an outburst of raucous laughter and even sniggers from the court audience immediately following. However, serious really is the name of the game overall here as A Woman Judge moves into its second thematic and narrative section:

This second part/half of A Woman Judge is heralded by the death of a supporting character – perhaps as a result of foul play; perhaps with Jin-suk being the true intended target. The majority of the subsequent narrative focuses on efforts to unveil the supposed perpetrator and the trial to bring them to justice and though this section’s ultimate outcome is eventually shown to indeed relate to the themes of the first ‘part’ (underlining how events allow Jin-suk to finally cement her position in the family as a wife with a worthy career and her place within society as a forward-thinking, modern woman) the change in tone from insightful, societal drama to murder/mystery thriller does, for a time at least, make A Woman Judge feel somewhat like two separate films spliced together. That's not a huge criticism particularly but it is noticeable nonetheless to the extent that that switch in focus, style, genre and depiction rather remains in the mind even as the overarching, linking themes are finally revealed and leaving a feeling of jarring digression to a degree.

|

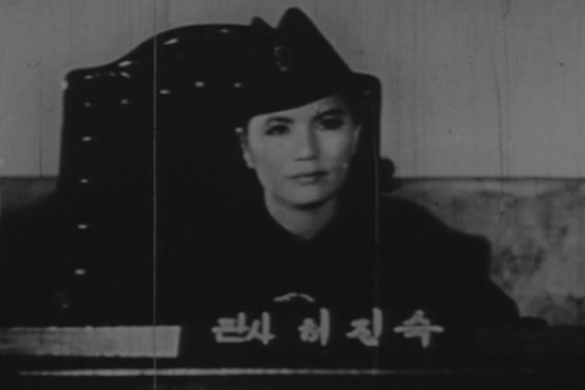

As was sadly the case for a great many Korean films of the Golden Age and earlier, A Woman Judge was for decades lost with no prints believed to have survived. However, in 2015 a rather well used and fairly worn 16mm print surfaced which the Korean Film Archive acquired, subsequently restored (as much as was possible with such a damaged print), digitized and made available on the KOFA YouTube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXfHTj754oU

Of course , a 16mm print has a much smaller original frame size than a 35mm or 70mm frame and as such the image is noticeably ‘softer’ and far from pin-sharp. There are also numerous scratches (some small and passing, others more severe and continuing) throughout the film. Not only that, but a couple of scenes had portions so damaged the offending moments had to be removed and the two ends spliced together (if you will) but the Korean Film Archive has done an absolutely superlative job of making sure viewers can easily understand the entire narrative in spite of this. For example, one scene ends rather abruptly with a character still needing to speak a final line of dialogue, but even though that dialogue line’s audio and visuals are missing KOFA provides the relevant subtitles anyway, so audiences are fully aware of what was originally said. Aurally, things hold together fairly well with issues being little more than a few crackles and noise, but nothing that prevents anything from being heard.

All in all, though this 16mm print was in pretty bad shape, none of the above issues interfered with my immersion in the narrative and though KOFA even includes a disclaimer on its YouTube channel about the severe damage the print suffered over the years, viewers should ultimately be wholly grateful for the work the Archive has undertaken to make A Woman Judge available to Korean film fans in as good a state as was possible, making sure the narrative is entirely understandable in spite of any scene parts missing in the process.

|

Director Hong Eun-won first became involved in the Korean film industry after becoming a member of the Shin Kyung Music Choirs in Manchuria and there meeting director Choi Yin-gyu. Working as a continuity girl for director Choi for over a decade, she progressed to the roles of script supervisor and eventually assistant director for a number of films through the late 50s and early 60s. A Woman Judge was her first feature as director – made when she was 40 years old – and in fact the film was at its time of release only the second Korean film ever helmed by a female; the first being Park Nam-ok’s 1955 highly respected drama A Widow. Throughout her career, Hong Eun-won repeatedly stated that her primary desire was to make and tell stories of the lives and struggles faced by (at that time, contemporary) women in Korea from a female perspective within an almost wholly male-dominated industry. In terms of such, A Woman Judge can truly be considered as the accomplishment of that goal, certainly if we especially focus on the somewhat more thematically in-depth first half, and its narrative overall stands as far more worthy than the veritable slew of male-directed melodramatic tearjerkers that were streaming out of Korea at the time. In fact, A Woman Judge sits far more closely to films now deemed to be classic examples of Golden Age Korean cinema helmed by masterful directors such as Kim Ki-young and the like and for a female director's feature debut that really is saying something.

Considering the number of current female Korean directors I’ve personally spoken to about film-making challenges – each and every one of whom has talked at length about the huge difficulties faced by women in the still male-dominated Korean film industry, both in terms of getting productions green-lighted and funded and indeed subsequently released – I can only imagine how near impossible it was for directors like Hong Eun-won and Park Nam-ok working as women in a far less enlightened age. As such, huge credit should be given to Hong Eun-won for succeeding in directing a further two films after A Woman Judge – A Single Mom (1964) and What Misunderstanding Left Behind (1966). However, though each were as thematically worthy as her debut film, audiences and indeed critics at the time gave her work little attention and it wasn’t until many years later that accolades for her films started to appear. That in itself combined with the aforementioned difficulties faced by women working in and on Korean films during the Golden Age likely played a part in nudging her towards screenwriting and away from directing in the very late 60s and may well have been a factor in her departure from the industry entirely after 1970, whether by deliberate design or circumstance. That, to my mind, is a pity to the nth degree and a huge loss to both classic Korean films as a whole and to the Korean film industry’s history which she frankly should have been a far bigger part of.

|

Summary:

Though Hong Eun-won’s A Woman Judge does for a time feel somewhat like two separate films spliced together, it nonetheless stands far closer to classic Golden Age films helmed by masterful directors such as Kim Ki-young and the like than to the plethora of fairly throwaway male-helmed melodramas that rather pervaded Korean cinema output at the time; made all the more important by the fact that it was only the second ever Korean film to be directed by a female.

A WOMAN JUDGE (여판사) will be screened on 10 November at the Close-up Film Centre as part of #LKFF2019.

Tickets:

https://www.closeupfilmcentre.com/film_programmes/2019/lkff-a-woman-judge/

여판사 A Woman Judge (1962)

Director: Hong Eun-won

Starring: Moon Jung-suk

|

All images © Korean Film Archive (KOFA), Korean Film Council (KOFIC)

Review © Paul Quinn

|

| |

|

LKFF2019 Review #3:

|

"You killed another one? What's wrong with you?

Cant't you keep them alive for more than a month?

Don't bother the neighbours, go and bury it properly..."

Synopsis:

As diabetes sufferers increasingly complain that a medication from pharmaceutical company Human In Bio is causing serious side-effects, one such victim (Jung Ga-ram) who has turned into a fully-fledged, flesh craving zombie staggers into the small rural village of Poongsan, situated in the ‘boonies', as locals put it. Soon facing off against and indeed fleeing from an aggressive-looking, slobbering dog he takes refuse in a nearby dilapidated gas station where he is quickly discovered by the owner's father, Man-deok (Park In-hwan) whom he straight away takes a bite out of.

On realising the man is one of the walking dead, the gas station owner, Joon-geol (Jung Jae-young), and the rest of his family fear their father will soon become undead too but instead he not only retains the ability to speak but also starts to look and feel much younger and healthier. Other elderly locals also notice the sudden spring in Man-deok’s step and begin offering him money to share the secret of his newfound vitality leading him to realise he could make a load of easy cash by getting the zombie to bite each and every one of them.

However, he is blissfully unaware of the absolute carnage he is about to unleash...

Review:

Familial dysfunction has long and regularly been a core element of numerous Korean film narratives, not least in the comedy genre. Whether you consider New Korean Cinema wave classics of the 90s and early 2000s such as The Quiet Family or Just Do It or look at more recent comedic endeavours like The Fox Family and Boomerang Family, for example, thematic similarities exist pretty much across the board regardless of a specific film's individual narrative. Character quirks, eccentricities, incompetence and/or inadequacies more often than not form a springboard from which the majority of the humour present stems, in the process shaping the characters' often ill-considered choices, actions and follies (often in the pursuit of money even if getting it means scamming others) which in turn ultimately bring them together as a cohesive family unit.

All of that is certainly the case in The Odd Family but while many Korean film fans will be aware there are many similarities in the dysfunctional family elements to those seen in very well known and indeed classic films such as some of those mentioned above, the intelligent intricacies of the genuinely funny humour and dialogue attached to them, for me, made them a joy to watch, feeling familiar with a certain amount of originality rather than simply appearing as a rehash of what’s already been done – whether you consider Joon-geol’s constant, repeated stressed-out mutterings to himself in criticism of other family members (“A pregnant woman shouldn’t be allowed to use words like that”; “Aren’t we going to have meat to celebrate this rare gig? Jeez, I’m sick of it! She’s virtually a vegetarian!”) and indeed the bickering between them; look at his hugely violent interactions with the zombie who he of course considers an unwanted outsider, all followed with a pleading “I didn’t mean to do that” (he knocks him off a bridge with his truck; he fly kicks him into a wall with a spike that impales him; and kicks and punches him off his young sister, Hye-geol (Lee Soo-kyung), thinking he’s trying to bite her when in fact the interaction between the two is a cross between a desire for cabbages (yes, cabbages) to quench a virtual addiction and almost a romantic interlude); or if you indeed think about the changing feelings of Hye-geol for the zombie (whom she names Zzongbie), moving from treating him almost as a pet in the wake of inexplicable death after death of rabbits in her care to a relationship of sorts far warmer and more loving than that she feels about any of her actual family.

And while we’re on the subject, how can a relationship build or have any chance of working when it’s between a young woman and a zombie? Well, that’s where narrative originality once again comes into play and in fact forms the basis for the film’s entire climatic conclusion, saucepans on heads n'all.

|

Director Lee Min-jae also pays homage in The Odd Family to some hugely well known, lauded and successful Korean horror/thrillers from the very biggest names: For example, following The Odd Family’s opening credits (accompanied by visuals showing Zzongbie crawling out of a manhole in a secure fenced area while audio media broadcasts explain the zombie virus having been created by Human In Bio’s dubious drug trials), we are taken late at night to a road of numerous accidents where a couple have a tyre blowout as a result of sharp tacks strewn in the road. They are soon approached by a shadowy figure in a large raincoat with a hood hiding his face who tries to open the locked car door with the now terrified inhabitants quaking inside.

The man turns out to be Joon-geol who 'just so happens' to be in the area (the implication being that he’s responsible for the tacks in the road, using the accidents caused as a way of scamming expensive repairs from unaware car owners) but before we discover that he is the seemingly ominous but ultimately comical figure his approach and actions outside the car are so reminiscent of an early scene from Kim Jee-woon’s I Saw the Devil (where Choi Min-sik approaches the car of Lee Byung-hun's fictional wife before breaking in, knocking her unconscious and abducting, killing and cutting her up) that comparisons can hardly fail to be made.

In fact the similarities are such that I guarantee the scene's use is both a means of deliberately setting up an initial creepy feeling by an overt nod and a wink film reference (allowing him to deftly turn it to parody when Joon-geol’s grinning face is finally revealed) as well as serving as a hat-tipping tribute to a now classic Korean horror, as it were, rather than being any sort of cinematic plagiarism, if you will.

|

Lee Min-jae is also obviously aware that virtually any discussion of a Korean film featuring zombies can hardly fail to reference Yeon Sang-ho’s box office smash Train to Busan and as such he again tips his hat by having the odd family watch a scene from the film on a smartphone when Joon-geol’s younger brother is explaining what a zombie is.

However, while these overt references work like a charm and will easily put a smile on the face of virtually any Korean film fan, the true strengths of The Odd Family are in its warmly quirky narrative peppered with constant tiny moments of genuine hilarity; the genuinely funny eccentricities of its various characterisations; the perfectly deadpan delivery of gently comedic, idiocentric dialogue by (especially) actor Jung Jae-young and actresses Uhm Ji-won and Lee Soo-Kyung; and indeed the success of taking a zombie based story in a somewhat unexpected and wholly tongue in cheek direction.

Just make sure you have a cabbage handy in case you get peckish and keep a saucepan nearby for any head protection needed.

|

Summary:

The Odd Family: Zombie on Sale is inherently and deliberately silly but that fact in itself is a plus point in this case and any film fans (Korean or other) looking for a couple of horror/comedy hours of sheer tongue in cheek, genuinely funny zombie escapism could do a lot worse than check it out, regardless of whether they have a cabbage addiction or not.

THE ODD FAMILY: ZOMBIE ON SALE (기묘한가족 / 2019) will be screened on 8 Nov at Picturehouse Central as part of #LKFF2019.

Tickets:

https://www.picturehouses.com/movie-details/000/HO00010030/lkff-2019-the-odd-family-zombie-on-sale

THE ODD FAMILY: ZOMBIE ON SALE (기묘한가족) / 2019

Director: Lee Min-jae

Starring: Jung Jae-young, Uhm Ji-won, Lee Soo-kyung

|

All images © Megabox Plus M

Review © Paul Quinn

|

| |

|

LKFF2019 Review #2:

|

Synopsis:

Peppermint Candy is a South

Korean film from 2000, directed by Lee Chang-dong (Green Fish, Oasis, Secret Sunshine),

which tells the poignant tale of a man's life and the factors that

lead to his demise. The main character's story is told in a series

of vignettes which also reference South Korea's difficult transition to democracy during the period and the turmoil faced by both him and his country ultimately has far

greater consequences than he could ever have anticipated.

|

Review:

The film's scenes run

chronologically in reverse order, from present day back through

time, to finish 20 years in the past:

The first scene we see is set

in the spring of 1999, where a group of former high school friends

gather at a riverbank for a reunion picnic. A man wanders into the

scene and the revelers recognize him as Yongho (Sol Kyung-gu), a

friend whom they had lost touch with years previously. As they

attempt to welcome him they increasingly see that his behaviour is oddly erratic

and, as they watch,Yongho climbs onto a railroad bridge and jumps in

front of an approaching train,

shouting out "I'm going back!" just before the train hits him.

Each successive scene (signalled

by a train travelling backwards) further expands the story of Yongho and

delves into the factors which led to his suicide.

In the first of these his wife Hongja (Kim

Ye-jin) has left him, he's in debt and has acquired a gun to shoot

himself but, before he can, he learns that the love of his life, Sunim

(Moon So-ri), is on her deathbed and has asked to see him one last

time - which leads to an incredibly moving scene of them together in

the hospital, and also explains the significance of the film's title.

|

The story then continues to jump back

through time to 1994, where we find Yongho running a small business, in the midst of his increasingly unhappy

marriage to Hongja, and having an affair with his one of his employees. A

chance meeting in a restaurant (where Yongho has an encounter with a figure from

his past) then leads into the film's next sequence, set in 1987,

where Yongho is a policeman who beats and tortures confessions from

suspected government dissidents. Hongja is pregnant with their

daughter but it is clear that he is driving her to leave

him.

When we see Yongho in 1984, he is a rookie cop who becomes traumatized following his first beating of a

suspect in order to get a confession, but the moment that really sets the course for his demise comes in

1980 when, as a soldier, his unit is called on to quell a civil

disturbance and he ends up making a fatal error of judgement.

|

When the film reaches

its end (at the beginning of the story) the year is 1979 and the

setting is the same riverbank seen at the beginning of the film. The

picnickers (including Yongho) are all together discussing their

hopes and dreams for the future.Yongho is clearly a happy and

optimistic young man who dreams of being a photographer and spending

his life with Sunim, the woman he truly loves.

Unfortunately,

having already seen his future, we know that all of his dreams will

disintegrate, he'll lose the love of his life (in more ways than one) and

he will end up a shattered man, lonely and heartbroken on the same

riverbank twenty years later.

Summary:

Peppermint Candy is a masterful and compelling

film which shows how innocence, hopes and dreams can so easily be

lost before the heart even realises what is happening.

Story Background:

The most important turning point in

the development of Yongho's character, during his time as a soldier, is set against the backdrop of the Gwangju

Massacre. This important landmark in the South Korean democratic

movement, in which a clash between government troops and student

pro-democracy demonstrators resulted in 200 dead (mostly civilians),

would result in the arrest and imprisonment of two former South

Korean presidents and echo through the country for years to come.

The Gwangju Massacre is also thought to have triggered the rise of

anti-American sentiment, and it is claimed that the Reagan

administration had strongly endorsed the use of force in quelling

the riot.

During the Eighties, we see Yongho's character

being hardened by the brutal tactics employed by the police at the

time - which was a turbulent period for South

Korea under the leadership of General Chun Doo-hwan, whose

dictatorship kept the country in a state of martial law and blocked

all efforts towards reform.

Finally, in the

Nineties, we see Yongho riding the wave of economic expansion

brought about by the new constitution of 1988, only to come crashing

down during the economic crisis of 1997 when investors abandoned

the debt-ridden South Korean economy, the currency rapidly

depreciated and the country was ravaged by soaring unemployment and

bankruptcies.

However, it should be noted that knowledge of the relevant Korean history is

not needed to enjoy the film, as the situations are fairly self

explanatory on a general level.

Cast & Crew:

Sol Kyung-gu plays the character of

Yongho with incredible depth and makes the character interesting

(and even charismatic) even when we are seeing the portrayal of the

monster he becomes. His innocence and naivety as a young man come

through beautifully and it is almost hard to believe that it is the

same actor. The rest of the cast play very much in the background to

the main protagonist but note should be made of Moon So-ri's

portrayal of Sunim especially in the heartbreaking deathbed

scene.

DVD

Region 1 YA

Entertainment Release

- Actors: Sol Kyung-Gu; Moon So-Ri; Kim Yeo-Jin

- Director: Lee Chang-dong

- Format: Color, Digital Sound,

Dolby, DVD-Video, Full length, Letterboxed, Subtitled, NTSC

- Language: Korean

- Subtitles: English

- Region: Region 1

- Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

- Number of discs: 1

- Rating: Not rated

- Studio: YA Entertainment

- DVD Release Date: August 17,

2005

- Run Time: 129 minutes

PEPPERMINT CANDY (박하사탕 / 1999) will be screened on 3 Nov at Regent Street Cinema, London, as part of #LKFF2019.

Tickets:

https://www.regentstreetcinema.com/programme/peppermint-candy/

|

All images © YA

Entertainment

Review © P. Quinn

|

|

|

LKFF2019 Review #1:

|

"Why should I feel sorry? Shouldn't mum and dad be the ones feeling sorry?

What did they ever do for me? How dare they just die like that. Why did they have to die and make my life so hard?..."

Synopsis:

Nineteen-year-old Young-ju (Kim Hyang-gi) has been the guardian of her younger brother, Young-in (Tang Jun-sang), since both their parents were killed in a car accident five years ago. Struggling on a daily basis to even put food on the table, she not only receives no help whatsoever from her other relatives but also has to fight her aunt and uncle's repeated attempts to sell her apartment.

When Young-in is arrested for his part in a robbery with a group of other boys, the families of the guilty agree to settle out of court to the tune of $3,000 each, forcing Young-ju to approach her aunt in the hope of borrowing the money. Her aunt’s flat out refusal to help – in the process telling Young-ju she wants nothing more to do with her or her brother – pushes the teen well past the end of her tether and as she breaks down in tears at home she stumbles upon documents from the criminal trial of the man who killed her parents which include his name and address. Noting down his details Young-ju sets out incensed, determined to take her revenge on the man she blames entirely for everything that is wrong in her life...

Review:

Young-ju opens with a short dialogue between the titular character and her brother. In spite of lasting less than two minutes before fading to black accompanied by a gentle piano melody bordering between melancholic and sweet (moving from one to the other on being repeated as a musical motif, depending on the darkness or lightness of specific story parts it accompanies), this brief interaction not only succinctly explains that both their parents are deceased (pointed to further shortly after by Young-ju’s decision to put the black framed funeral photos of her mother and father in pride of place on a lounge altar for their memorial) but also underlines her sole guardianship of her little brother and indeed her deep love and caring for him regardless of his obvious tacit and sullen demeanour, her supportive feelings not least screaming out of actress Kim Hyang-gi’s nuanced and wholly natural facial expressions as Young-ju playfully tries to force an extra chicken drumstick on him.

Those background facts and character traits so quickly placed in viewers’ minds, the narrative is then free to focus on her daily physical (financial) and emotional struggles within an absolutely palpable air of isolation. Repeatedly in the early stages of the film, visual depictions show Young-ju standing on her own, head bowed, or indeed crouching head in hands utterly alone, whether in various alleyways; outside or inside her home, and whether you consider her efforts to deal with Young-in's acting out (all the while trying to show him love and support) or indeed look at her discussions with her deeply condescending aunt one thing is blatantly clear, that is her wholly negative interactions and failure to connect (through no fault of her own) positively scream that she is utterly, miserably alone with no-one to turn to whatsoever, having been forced into adulthood while still a child without any of the support a young woman needs to do so and be able to cope.

|

Young-ju’s aunt consistently refers to her move from childhood to adulthood negatively and critically believing as she does that Young-ju has failed to make the move fully or adequately in spite of the fact that her utter lack of support for her niece is largely to blame for the very problems she claims to see – “You’re almost adult age so it’s time you started acting like one"; “You’re just a naive baby"; “You’re just kids in adult bodies”, etc. These cutting barbs at one point cause Young-ju to respond “I’m no longer a child, so I don’t need a mom” but as we (and she) are soon to discover that is exactly what she needs more than anything else, and indeed always has needed to allow her to blossom into womanhood naturally as her maturity grows rather than having her childhood stripped away and the weight of the world placed on her all too young shoulders.

The maternal figure Young-ju subconsciously yearns for (even if she doesn’t fully realise it herself) comes in the form of the boss of a tofu shop where Young-ju begins working and while this middle-aged woman, Hyang-sook (Kim Ho-jung), also regularly refers to Young-ju as not being fully a woman yet it is from a fully supportive, loving and even celebratory perspective (“There’s no need for my baby to cry”; “My Young-ju will be able to achieve anything she sets her mind to"; “My Young-ju isn’t like other kids today, she’s shrewd and good natured”) and no sooner than these celebration of Young-ju’s youth begin than changes in her demeanour come in a marked and almost instantaneous fashion: Cries of misery and desperation become tears of joy; and a hung head with an avoidance of eye contact becomes a raised, glowing and smiling face bathing in meaningful connection.

At one point in proceedings, Young-ju is shown crouched down at the Han River bridge crying for her mom and you can absolutely guarantee it’s not her deceased blood relative she’s referring to.

It’s regularly said that kids today grow up far too quickly. Director Cha Sung-duk's narrative for Young-ju deftly and definitively shows what can happen to the heart and soul when they’re forced to, and in an absolutely gripping manner throughout.

|

Young-ju (the film) adds yet further thematic depth with its discussion of perceptions and changing opinions in the wake of full understanding, disclosure, blame and guilt in terms of Young-ju’s feelings about the man who killed her parents in a truck accident, his family and indeed their thoughts about her. Fear of (pivotal) spoilers keep me for being anything other than vague on this subject but rest assured such thematic statements are a driving force of the entire story; are pivotal to the success and believability of the other aforementioned themes; and are indeed vital to the film’s deeply moving ultimate conclusion.

If proof were needed that references to such changing attitudes and opinions infuse the film’s even tiniest of moments, one need only look at two scenes in which Young-ju is given food from the tofu shop to share with her family. In the first, she carries the black plastic food bag to an alley on the way to her apartment and unceremoniously dumps it into a pile of roadside rubbish. In the later second scene, she carries the food back with a look of gleeful appreciation on her face, her emotion changing to virtual trepidation as her walking slows to a standstill as the home she realises she no longer wants to return to comes into view.

Young-ju premiered at the Busan International Film Festival and though it did subsequently have a theatrical release it was shown on only one Korean cinema screen for a very brief period. One, I guess, should at least be pleased that Young-ju reached the cinema at all when so many other small independents are frankly ignored outside of the festival circuit, but such a fleeting, blink and you’ll miss it appearance is nonetheless an absolute shame for this is a strong, accomplished, multi-layered tale from a confident female director that is wholly deserving of being seen and appreciated by all fans of exemplary cinema, Korean or other, never for a moment appearing to be the debut feature it actually is.

|

Since her days as a child actress in the early 2000s, Kim Hyang-gi has forged a career that has brought her numerous accolades as an acting talent to be reckoned with. Largely coming to the attention of critics and public alike as a result of her roles in 2012’s A Werewolf Boy and 2013’s Thread of Lies, she has since consistently shown through remarkable performances in critically acclaimed films such as Snowy Road and Innocent Witness, as well as record breaking box office hits such as Along with the Gods, that she can as easily hold an entire film by her acting talent alone in lead and co-lead parts as she can provide a steadfast base for those around her when playing a supporting role.

As far as Young-ju is concerned, Kim Hyang-gi frankly owns the film from start to finish, her frankly jaw-dropping performance increasing the film’s strength and memorability to the nth degree. Each and every tear is genuine, every cry is affecting, every smile utterly uplifting and even when she says nothing she is always speaking volumes.

Case in point: Caught unawares in a place she shouldn’t be, the character of Young-ju hides lying on the floor behind a veil surrounding a bed, as two others discuss her in the wake of a revelation (from their point of view), not knowing she’s there able to hear and listening. For the scene, Kim Hyang-gi was required to lie absolutely motionless with the camera fully face-on for over two minutes – not flinching, not blinking nor seemingly even breathing as she’s left speechless by the enormity of what she shouldn’t even be hearing. So successful is she in achieving this seeming abject paralysis that I for a time began to ask if the director had perhaps used a still image accompanied by audio, that is until someone turned a light off at the near end of the segment showing it was indeed live action. Not only frankly astonishing but also absolutely unforgettable, this scene is nonetheless just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the sheer emotive power of Kim Hyang-gi’s breathtaking performance as the titular Young-ju throughout the film’s entire running time.

Summary:

Though Young-ju is her debut feature, Cha Sung-duk brings a directorial confidence to this hard-hitting yet gently poignant drama that ensures it wholly succeeds an emotive powerhouse from start to finish, helped yet further by a remarkable, stunningly nuanced performance from actress Kim Hyang-gi.

YOUNG-JU (영주 / 2018) will be screened on 2 Nov at the Rio Cinema, Dalston, as part of #LKFF2019.

Tickets for the screening can be booked on the Rio's website via this link.

YOUNG-JU (영주) / 2018

Director: Cha Sung-duk

Starring: Kim Hyang-gi, Kim Ho-jung, Yoo Jae-myung, Tang Jun-sang

|

All images © CGV Arthouse

Review © Paul Quinn

|

| |

|