Synopsis:

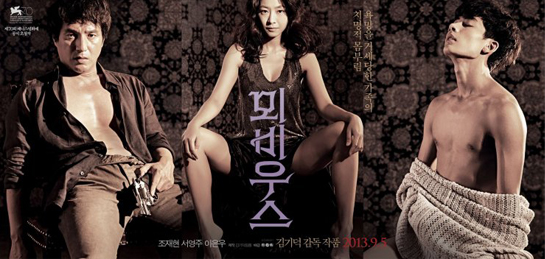

On discovering that her husband has been having an affair, the (unnamed) wife and mother of a family (played by Lee Eun-woo) tries to castrate him while he sleeps. Failing in her attempt, in an unbalanced and vengeful rage she sneaks into her son's room and mutilates his genitalia, instead. While the boy (Seo Yeong-joo) does his utmost to hide his resultant disfigurement from his peers, his father (Jo Jae-hyeon), racked with guilt and blaming himself, endeavours to find a solution to his son's problem and ascertain a way for him to have a normal life and be able to achieve sexual gratification, in spite of having no manhood.

In the meantime, gradually becoming rather enamoured with his father's mistress, the boy inadvertently gets drawn into a vicious gang rape with a number of thugs - being sentenced to a term in prison, as a consequence - and by the time he is released, his father has decided that the only solution is to have his own manhood removed and transplanted onto the young man.

However, far from solving anything, that decision brings its own dark, twisted and even incestuous problems that threaten to put an end to the family unit once and for all...

|

|

Review:

Kim Ki-duk is without question one of if not the most controversial of directors working in Korean cinema today. Throughout his entire career, his always uncompromising, often searing and regularly shocking film narratives and provocative themes have equally brought him both an ever-growing legion of ardent fans proclaiming his genius (especially Internationally) and an army of vehemently outspoken detractors not only citing alleged misogyny as being virtually inherent to his sexually-charged storylines but also taking issue with specific character motivations and, in their eyes, dialogue 'clumsiness'. In fact, so vocal has the Domestic criticism of Kim Ki-duk's work been over the years that he was at one point driven to state he would no longer release any of his films in the Korean market; at another being somewhat pushed into self-imposed 'exile' deep in the Korean countryside - ultimately allowing the creation of his cathartic 'Arirang', leading to the subsequent release of 'Amen', and finally bringing his return to grace and favour within the Korean film industry as a result of last year's 'Pieta'. I personally am one of the (I assume) minority standing firmly between fans and detractors of the director; both seeing great merit, even vision, in some of Kim Ki-duk's work yet taking issue with some of the elements within and their realisation. However, whether or not you are a fan of the director's work, the one thing you can be sure of with any new Kim Ki-duk film is that you can never be sure exactly what to expect, but you can almost be guaranteed a narrative as thought-provoking as it is shocking, and vice versa.

Discussing 'Moebius' recently, Kim Ki-duk said his intention was to show the three main characters of father, mother and son connected like a Moebius strip - an endless twisted loop, the end of which is also its beginning - and as such the thematic idea (in a manner of speaking) of history doomed to repeat itself looms large throughout the tale.

The 'family' unit in 'Moebius' is certainly twisted to say the least and its various interactions incestuous, almost by definition and/or default:

The father taking a mistress, the character of whom is played by the same actress as stars as his wife, not only speaks of adulterous deeds laying beneath outward normality but also screams of male adulterers being drawn to women who subconsciously remind them of their spouses in essence; the son's subsequent sexually-charged involvement with said mistress both references the idea of a Freudian Oedipal complex (him being attracted by a woman reminiscent of his mother) and brings with it comparisons to the Classical mythological story of Oedipus itself - a man who killed his father, married his mother and had two children by her. It could even be said that the son's ultimate sacrifice of his manhood is an even darker retreading of Oedipus' decision to gouge out his own eyes, but if at any point in proceedings you begin to ask just how ingrained Oedipal themes really are to Moebius, they are underlined to the nth degree in the concluding stages with the son's inability to become aroused by anyone (or anything) other than his mother and by his sexual gratification by her hand, both figuratively and literally.

|

|

As far as the mother figure is concerned, as well as serving all the above themes and elements, her character arc largely centres around not only the aforementioned idea of history repeating itself but also its utter inevitability in spite of choices made and actions taken specifically with the intention of thwarting its occurrence.

In the early stages of 'Moebius', after failing in her attempt to castrate her husband, her decision to instead mutilate her son's genitalia at first seems either, at best, simply the workings of an unbalanced mind grasping for revenge or, at worst, just the latest example of Kim Ki-duk jarringly twisting actions and motivations for no other reason than to place specific characters in positions of suffering. However, as the various themes in 'Moebius' are more fleshed out, and even reiterated, it becomes increasingly clear that her vicious act is made in an effort to prevent her son from being able to follow the same path as his father; her choices and actions perhaps even causing the very repeating of history they were meant to prevent - unavoidable fate, if you will.

That idea is taken to its ultimate conclusion later in the film with mother and son becoming sexually and incestuously involved; once again coming to pass partly as a result of the mother's original violent act of castration and partly because of her need to assuage her guilt as the cause of his inability to find sexual gratification. In short, regardless of the misguided preventative efforts she makes or the damage limitation she attempts, her actions are ultimately a self-fulfilling prophecy looped in a never ending Moebius strip.

Religious references, imagery and iconography also play a fairly significant role in 'Moebius' - a sole figure bowing to a head-cast of Buddha in a shop window; the knife used for the castration kept below a Buddhist bust etc. - but, of all the themes present, the underlying statement of enlightenment only being possible with the removal (again, in this case, both figuratively and literally) of sexuality is, to my mind, the least effective. Sure, the idea is there clearly enough but the religious elements largely feel passing and not enough room is allowed to enable them to be given more depth or lasting meaning aside from the obvious. While watching 'Moebius' I couldn't help but consistently contrast the religious iconography with that in Lim Woo-seong's sublime 'Scars' - a film where Buddhist themes scream from every scene in which they appear; their meaning abundantly clear and utterly pivotal to proceedings throughout, without ever needing explanation. By comparison, the references in 'Moebius' really don't stack up to any noticeable level.

|

|

It does have to be said that each of the major themes of 'Moebius' has appeared in one or other of Kim Ki-duk's previous films - their combined featuring here feeling like somewhat of a compendium. That being the case, they largely work well together and while, for example, the idea of orgasm from physical pain (various characters in 'Moebius' seek sexual gratification by using rocks to scrape their skin to the point of blood-letting or by having a knife moved around in an open stab wound) is not as notable or shocking as its use in 'The Isle', 'Moebius' uses it to also add some twisted humour to the dark proceedings; thereby allowing the narrative to 'get away' with more farfetched concepts than would otherwise be the case. Not only that, but that dark humour adds to the aforementioned Oedipal themes to overall give a feeling of Classical tragedy-cum-farce in Ancient Greek or Roman theatrical style. It may seem strange for me to compare a Kim Ki-duk film to an R-rated 'Story from Ovid' but it does really sum up what 'Moebius' has to offer.

Finally, Kim Ki-duk's decision to make 'Moebius' completely devoid of dialogue is not only brave but also frankly inspired: Over the years, a consistent and repeated criticism of the director's work has been a perceived lack of nuance in his character dialogue and it almost goes without saying that some of his strongest characters have been those who have had no speech. By removing dialogue completely from 'Moebius', Kim Ki-duk not only side-steps that issue but also brings an immediacy to the character trials and tribulations; in the process wisely negating the need for expositional depth. We are in the moment throughout 'Moebius', even if that moment may contain both the present and the future.

Cinematically, 'Moebius' is a far smaller affair than Kim Ki-duk's 35mm cinematic pieces. Filmed entirely on a self-held digital camera and setup, the starkness inherent to the medium brings with it a much needed realism and even a feeling akin to seediness of a sort, fitting perfectly with the overarching narrative tale. Real fiction, if you will, though any mention of the less than inspiring Kim Ki-duk film 'Real Fiction' itself should probably be avoided at this point.

Summary:

Originally given a Restricted rating by the Korean Media Ratings Board, Kim Ki-duk's twisted tale of sex, religion, castration and incest subsequently underwent a number of cuts to gain a mainstream domestic cinema release. 'Moebius' is no less shocking as a result of those cuts.

Cast: Lee Eun-woo (mother), Jo Jae-hyeon (father), Seo Yeong-joo (son), Kim Jae-hong (thug)

Directed by: Kim Ki-duk

|