Essays / Talk Papers:

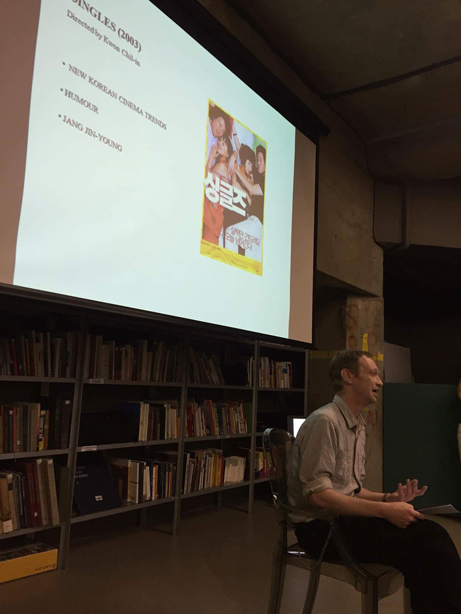

Hangul Celluloid's 'Singles' Introductory Film Talk at the University of Westminster (4 Mar 2019):

In early 2019, I was asked by the Korean Society of the University of Westminster to give an introductory film talk prior to a screening of 'Singles' (2003) as part of an International Women's Day event.

The following is a transcription of that talk:

Trends:

I'm not sure if any of you have checked out the synopsis of Singles online or wherever. The film tells the story of the friendship between two women and their various relationships - Nan is nearing her 30s and is pretty sure her life will take the traditional route of decent job and relationship leading to marriage, that is until she's dumped by her boyfriend and demoted at work, while Dong-mi is currently on her 48th boyfriend, is happy to tell anyone and everyone about her rather liberal attitude to life, relationships and sex and has no intention whatsoever of settling down.

The film was released 16 years ago in 2003, but even in 2019 it feels contemporary, wholly modern, to the extent that it could almost stand alongside Korean relationship comedies of the present day. But that fact in itself makes it all too easy see Singles as just another relationship comedy, one in a very long list, and overlook the part it played in huge changes that took place in Korean cinema in the late 90s / early 2000s, a period that's become known as the New Korean Cinema wave.

While the vast majority of discussions about the New Korean Cinema wave can almost be guaranteed to cite Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho etc. as directors whose films fuelled the entire expansion of Korean cinema - using modern filmmaking techniques, merging genres to create highly original films that had an impact both internationally and domestically - far fewer mention the many other New Korean Cinema directors who chose to focus on familiar genres and narrative ideas, bringing a progressiveness to already popular subjects and often imbuing their films with noticeably modern attitudes.

With many of these directors having been schooled abroad, they began to step away somewhat from traditional Korean depictions of relationships, love and romance – such as pre-marital chastity, relationships serving largely as a means to marriage, lasting happiness only coming within the standard ideal of ‘married family’ – and move more towards depictions of relationships as an end in their own right for young adults not yet ready for marital commitment, this more modern attitude coming at a time when young single Korean women were beginning to assert their individuality and become far more sexually aware and worldly wise than previous generations.

In Singles, the character of Nan being dumped by her boyfriend (thereby, in the early stages of the narrative, no longer having a relationship that could lead to marriage), having to learn to be single again, as well as the change in her attitude towards life and relationships as the film progresses can be seen as a mirroring of the gradual move from traditional to modern that that was taking place throughout New Korean Cinema at the time, and indeed in Korean society as a whole.

Of course, stories of sexually aware women pursuing their own needs and desires outside of marriage were certainly nothing new back in 2003, but for decades Korean films had dealt with such subjects as cautionary tales, with such women with wholly modern attitudes to life and sex shown as a threat to traditionalism, family and Korean society as a whole and ultimately punished for their 'wantonness'. Discussions of these sorts of depictions can almost be guaranteed to cite director Kim Ki-young as a driving force, and indeed he was absolutely obsessed with what he himself described as these ‘Despicable Women’ throughout the Korean cinema Golden Age of the 60s and 70s, whether you look at Io Island (1977), Insect Woman (1972), Woman of Fire (1971) or indeed his absolute classic The Housemaid from 1960, and on and on. However, while Kim Ki-young was pretty much the most famous director of such narratives, he certainly wasn't alone or indeed anywhere near the first to point to a supposed societal threat posed by modern female attitudes, autonomy and sexuality. Indeed, if you look further back to the 50s to films such as Madame Freedom or even way back to the 30s with Sweet Dream from 1936 you'll find an absolute myriad of such cautionary tales relating to female modernity. As well as themes, what all of these films across the decades had in common was the ultimate punishment of the wayward female in question. Whether she committed adultery, became obsessed with consumerism – her love of Westernised trinkets and clothing leading to her neglecting her family – or pursued sexual freedom, in the process turning her back on traditional female ideals, the outcome was the same – she would be made to pay dearly for her self-serving actions. In fact, the first ever Korean film where such a sexually voracious woman wasn’t ultimately punished in some form or other for her sexual actions and choices outside marriage was The Adventures of Mrs Park which wasn't released until 1996, just seven years before Singles.

Admittedly, those earlier depictions of independent, modern, sexually aware females looking out for themselves rather than focusing on marriage, husbands and family were much harder and forceful. These women were far more conniving, far more self-serving than the fun-loving independent women in films like Singles, but that's kind of the point. New Korean Cinema directors were essentially saying that modern women following their own needs, desires and pleasures was no big deal, it was just life and even something to be celebrated... and that struck a massive chord with female cinema audiences, making films like Singles hugely successful at the Korean box office.

Singles also utilises other popular New Korean Cinema trends, those of depictions of noticeable feisty females and a somewhat reversal of traditional male / female roles – i.e. strong women paired with far meeker, or even hapless, males. There was an absolute explosion in the appearances of these sassy female characters around the time of Singles and slightly before, the most obvious example being Kwak Jae-young's My Sassy Girl in 2001 with its story of a mild-mannered man’s relationship with a hilariously violent, virtually psychotic girl. This switch in gender roles combined with strong female characters was so popular with audiences (especially young women) that a slew of similar examples really had to follow, from the My Wife is a Gangster series of gangster comedy movies to romance Windstruck, to Saving My Hubby - the story of a woman’s fevered journey through Seoul to rescue her husband who has been taken hostage by a bar owner over an unpaid drinks bill, all while carrying her baby on her back. As time passed, the physicality of these sassy depictions mellowed somewhat turning largely to dialogue-based feistiness, resulting in much more realistic and natural narrative humour.

While many of the NKC comedies were aimed directly at those in their pre-marital late teens and early 20s, just as many targeted a slightly older demographic, allowing discussions of modern attitudes to marriage and sex to be included within the humour and speak directly to age groups for whom such issues really mattered. Such is the case in Singles, as well as, for example, The Art of Seduction (telling of a competition between a man and a feisty female to see who is better at seducing members of the opposite sex for a one night stand), A Bizarre Love Triangle (the title really speaks for itself) and, later, My Wife Got Married, in which a strong sassy woman married to a meek man decides she wants to marry a second husband while keeping her current marriage going.

Singles’ use of all of the above ensures that though the film is based on the Japanese novel Christmas at Twenty-nine, it is Korean through and through to the extent that it could almost be considered a poster film for New Korean Cinema comedies.

Ultimately, Singles was at the very forefront of changing decades-long depictions of women in Korean cinema to show modern female attitudes and sexuality in a far more positive and natural light than ever before, celebrating their modernity rather than punishing them for it, and the film's success ensured that such depictions snowballed in its wake. As such, in hindsight, Singles’ importance to Korean cinema as a whole cannot be overstated in any respect.

Humour:

It almost goes without saying that this reversal of traditional gender roles, either overtly or subtly, and the idea of noticeably feisty females easily lend themselves to humorous depictions and director Kwon Chil-in uses them to great comic effect in Singles combining them with genuinely witty dialogue throughout... whether it’s Dong-mi (Uhm Jung-hwa) dragging her trouserless boss across a office by his tie to loudly berate him in front of her work colleagues, or more traditionally feminine Nan (Jang Jin-young) undertaking a sexual liaison dressed as a bunny girl brandishing a whip, while her conquest is on all fours on the floor. This carries through to Nan's thoughts being shown and voiced on screen - on the outside she's shy, polite and respectful - as society would want her to be as a lady - while inside she's the archetypal feisty female, swearing like a trooper and happy to imagine herself beating up a woman in the street on hearing her talk happily about love.

While Singles is wholly modern, Kwon Chil-in nonetheless references a number of cinematic romance and drama clichés throughout, gently parodying them in the process... rain to represent a character's sadness, a 360 degree camera pivoting around two lovers etc etc and in each case Kwon Chil-in has one of the characters point out that it is a movie cliché, almost poking fun at himself in the process.

As a final note on the humour in Singles, there was somewhat of a trend during the New Korean Cinema wave for comedies to use overtly and overly ‘loud’ humour. Take for example Crazy First Love in which actor Cha Tae-hyun’s character spends the entire first half hour of the film yelling almost every line of dialogue at the top of his lungs, getting, as far as I’m concerned, more annoying and less funny with each passing second. Kwon Chil-in wisely avoids such overly contrived attempts at noisy humour in Singles and, by keeping things fairly bright and peppy as well as creating genuinely likeable characters that are easy to warm to, what boisterousness there is comes across as far more legitimate and indeed welcome, succeeding to a much funnier degree.

Jang Jin-young:

I’d love to give you an overview of all of the main Singles cast members but time is rather of the essence. So, instead, I’m going to briefly focus on one cast member specifically. That is, actress Jang Jin-young who in her nine film career was nominated for 21 acting awards, winning 14, quickly becoming one of Korea’s best loved actresses, in the process.

Jang Jin-young began her career in front of the camera as a model, and even represented her home province in the 1993 Miss Korea beauty pageant. She briefly moved from modelling to television acting in 1997 and in 1998 she landed her first film role in fantasy drama Ghost in Love. While her tough girl supporting role in Kim Jee-woon’s classic The Foul King in 2000 brought her to the attention of audiences and film critics far more than Ghost in Love, it was her first major starring role in 2001’s Sorum that truly set her on the path to stardom. Telling the story of a chain-smoking victim of domestic abuse who gradually begins to lose her grip on reality, Jang Jin-young’s jaw-dropping performance will at once break your heart and send a chill up your spine... and that performance quite rightly earned her six best new actress awards in Korea and abroad.

In 2003, Jang Jin-young starred, of course, in Singles for which she won another load of awards and Scent of Love – a film about a woman diagnosed with stomach cancer which tapped into New Korean Cinema’s penchant for films dealing with terminal illness. However, following a further two film roles which included the superlative Blue Swallow, a historical biopic about the life of one of Korea’s first women pilots, Jang Jin-young began to suffer from debilitating abdominal pain, and on seeking medical attention was herself diagnosed with stomach cancer, sadly mirroring the narrative of Scent of Love. Life cruelly imitating art, if you will.

She immediately retired from acting and began treatment combining Eastern and Western medicine but though she bravely battled against her disease for almost exactly a year, on September 1st 2009 Jang Jin-young passed away. She was just 35 years old.

During an interview at the time of Singles’ cinema release in 2003, Jang Jin-young said her character in the film had a personality closer to her own than any other role she’d ever played. As such, Singles is a beautifully, genuinely funny comedy that not only stands as a tribute to the talent of one of Korea’s best-loved actresses but also serves as an uplifting reminder of how warm, witty and full of life Jang Jin-young really was.

Enjoy the film.

Hangul Celluloid's 'The Red Shoes' Introductory Film Talk at the KCCUK (23 Feb 2017)

I was asked to give an introductory film talk prior to the KCCUK Korean Film Nights' 'Chills & Thrills' screening of 'The Red Shoes' (2005) on 23 February 2017.

The following is a transcription of that talk:

Introduction:

Tonight’s screening of ‘The Red Shoes’ takes us back to 2005 and the period that’s become known as the New Korean Cinema wave, a time in the late 90s and early 2000s that saw an influx of new, younger Korean directors – many of whom had studied abroad – using the latest film-making techniques within the easing of film censorship to take Korean cinema in wholly new and highly original directions, allowing Korean film to explode onto the international stage, in the process.

Prior to this period, the horror genre was pretty much a hard sell in Korea and while some of Korea’s horror output over those years is now deemed to have been both classic and hugely influential for Korean cinema as a whole – for example, Kim Ki-young’s use of horror ideas and elements in the 60s and 70s within his depictions of what he described as “despicable women”; Shin Sang-ok’s groundbreaking 1969 cinematic take on the legend of the gumiho or nine-tailed fox, ‘Thousand Years Old Fox’; or Go Yeong-nam’s surreal and almost experimental 1981 film ‘Suddenly in the Dark’ – the Korean horror genre was nonetheless far from the powerhouse it would later become as a result of the New Korean Cinema wave.

That change largely began with the release of Park Ki-hyung’s ‘Whispering Corridors’ in 1998, continuing with ‘Memento Mori’ in 1999 and ‘Wishing Stairs’ in 2003. This series of girls’ school horror films spoke directly to a far younger audience than those who films had been aimed at prior to New Korean Cinema and with similar shifts in audience demographics taking place in other genres, young adults began to flock to cinemas. In short, these films were a huge success not just for the horror genre but for Korean cinema as a whole. They not only awakened a desire in viewers to see more horror films featuring characters they could directly relate to in either age or situation (the horrors of school, the pressure of studies, the difficulties of relationships) but also shone a light for the film industry to finally see that horror could be a driving force in the expansion of Korean cinema as a whole.

Based loosely on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale of the same name, The Red Shoes tells the story of a young woman called Sun-jae who finds a pair of beautiful shoes mysteriously abandoned on a subway train. Immediately drawn to them, she is wholly unaware that her inability to resist taking the shoes home is the result of a sinister curse that exerts its power over all who come into contact them. Soon Sun-jae and her young daughter, Tae-soo, become bitter rivals for possession of the shoes as the curse takes bloody revenge on anyone trying to steal them.

In the years directly preceding, and indeed following ‘The Red Shoes’, there were numerous Asian horror films focused on, or strongly featuring, similarly deadly or malevolently possessed objects, and Korea was no exception: Phone (2002), in which a journalist who has broken a paedophile story begins receiving anonymous calls on her new phone that seem to change her daughter’s personality; Unborn but Forgotten (2002) which tells the story of people dying after visiting a website; the prominent featuring of a Ouija board at the start of Dead Friend’s (2004) tale of ghosts and possession; The Doll Master (2004) featuring a doll quite a bit more animated than most; The Wig (2005) with its focus on a possessed wig, funnily enough; and even recent examples such as Don't Click, about a video that seems to kill anyone who watches it; and Killer Toon (2013) - also directed by Kim Yong-gyun, director of The Red Shoes - in which a female horror webtoon artist discovers that everything she draws is taking place in real life... and the list really does go on. So much so, in fact, that these types of tales almost form a sub-genre in their own right.

With its horrific story of seemingly possessed shoes – the specific colour of which we will discuss shortly – The Red Shoes fits neatly alongside these so called haunted object movies but director Kim Yong-gyun goes to decent lengths to raise proceedings above the norm, mainly in the case of Sun-jae’s fragile mental state. From the very outset of The Red Shoes, Sun-jae’s life is falling apart, even before she comes across the titular footwear. Her relationship with her husband is rocky to say the least, she’s trying to set up an eye care clinic with next to no money, and as she desperately tries to hold everything together she catches her husband having sex with another woman in her marital bed. As Sun-jae takes little Tae-soo and moves out of her home, Kim Yong-gyun repeatedly visually underlines her crumbling mental state by featuring dilapidated and rubble strewn buildings, namely the run down, claustrophobic apartment she moves into and the eye clinic which is at the very start of its renovation. Present day lighting and colours (or lack thereof) at the same time highlight the drabness of Sun-jae’s life without the shoes and contrast it with the always sumptuous, sometimes almost luminous colour and beauty of the shoes themselves. Not only that, but flashback scenes to the time of Japan’s occupation of Korea on more than one occasion appear almost sepia with the bright, shimmering high colour of the shoes or of a traditional dress being virtually the only colours present.

The horror set pieces work fairly well. Certainly, Asian horror fans will certainly seen some similar things before – I mean, who hasn’t seen an Asian film featuring a long-haired, white-faced ghost; or a female character peril in an ominous corridor with lights flickering on and off plunging the entire area into darkness for seconds at a time? – but even so, some of the other horrific moments in The Red Shoes - such as falling snow turning to blood - are frankly utterly inspired and deeply memorable.

You're lucky tonight to have an opportunity to see the uncut version of The Red Shoes. On being submitted for certification, The Red Shoes was given an 18 rating and as film companies in general were determined to entice young adults to cinemas (as already stated), Showbox demanded cuts to allow the film a 15 certificate. Though only a matter of minutes were cut for the theatrical release, the removal of that content changed the feel of the climax of the film significantly. In the cut version, in the latter stages as the main story thread appears to have reached its conclusion, The Red Shoes does seem to change tone quite dramatically to thriller, rather than classic or psychological horror, and though the final reveal explains that move, it does, at least temporarily, feel somewhat of an odd shift when it first takes place, jarring to a degree once more with the ultimate conclusion shifting back to pretty standard horror fare. The few minutes of extra narrative in the uncut version both eases that transition and allows the film to focus more on the far more important psychological aspects of Sun-jae’s fractured mind and the darker tone that creates.In short, the uncut version of The Red Shoes is a much superior film.

And so to talk of colour: In the first five minutes of The Red Shoes - in the very first scene, in fact - one thing will massively, instantly stand out. That is that the red shoes aren't red, they're pink. The reason for that is very simple: In Korea, The Red Shoes has long been known as The Pink Shoes. In 1948, a British cinema version of Hans Christian Andersen's fairytale was released. That film was shown in Korea in 1954 and the Korean distributors changed its title from The Red Shoes in English to The Pink Shoes in Korean. There has been debate for years as to the reason for that change: Some claim with the film being shown so soon after all the horrors of the Korean War that the distributors wanted to stay away from a colour associated with blood (a claim I tend to pretty much dismiss), while others believe the change was to make a subtle step away from the red associated with communism. However, there is another possibility: Over the years, the most inconsistencies in translations from English to Korean - in books, films and theatrical pieces - have been in terms of colours. For example, for a long time in Korea, Nathaniel Hawthorn's novel The Scarlet Letter was incorrectly known as The Orange Letter, and if you're aware of its story of betrayal and adultery it'll be pretty obvious to you that orange is entirely the wrong colour to reference, scarlet being the only colour that really fits. Whatever the ultimate reason for the change in title all those years ago from The Red Shoes to The Pink Shoes, the outcome is the same. Ever since, there has been a duality to Hans Christian Andersen's fairytale in Korea, with those who know of it being aware that its true title is The Red Shoes but still being just as likely to refer to it as The Pink Shoes because that's the title they grew up with.

As far as I'm concerned, the use of (if you will) innocent pink for the stilettos in Kim Youn-gyun's classic horror rather than erotic red works all the better to beautifully contrast the gentle look and beauty of these otherworldy shoes with the absolute horrors they cause.

As a final point, in 2001 Tartan Video launched the Tartan Asia Extreme label, releasing various horror films and thrillers from a number of Asian countries in the UK and US, the more intense the content the better. Asia Extreme was the entry point to Korean cinema for many international viewers, some of whom had hardly been aware Korea even had a film industry. Tartan's release of The Red Shoes in 2007 not only played a significant role in the film becoming, internationally, one of the most famous Korean horrors of the New Korean Cinema wave but also in it gradually becoming thought of as a classic of the genre. It does also have to be said that the Asia Extreme label was partly to blame for the misconception among many that all Korean films were inherently violent, but as far as I'm concerned the pros of what Tartan did for Korean cinema internationally far outweigh the cons.

I have talked your ears off for long enough and I'm sure you're all itching to see The Red Shoes.

So, thank you and enjoy the film.

|

Hangul Celluloid's 'Saving My Hubby' Introductory Film Talk at the KCCUK (15 Sept 2016)

I was asked by the Korean Culural Centre UK to give an introductory film talk prior to the KCCUK 'Korean Film Nights' screening of 'Saving My Hubby' (2002) on 15 September 2016.

The following is a transcription of that talk:

Introduction:

Tonight’s screening of Saving My Hubby takes us back once again to 2002, almost slap bang in the middle of the New Korean Cinema wave of late 90s and early 2000s. The film tells the story of Geum-sun and her husband Ju-tae, a young married couple with a six month old baby. As Geum-sun desperately tries to juggle looking after her husband, raising her child and trying not to disappoint her mother-in-law, she receives a phone call telling her that Ju-tae is being held hostage by a bar owner over an unpaid drinks bill and won’t be released until it is paid. Realising it’s up to her to save the day and having no-one to look after her baby, Geum-sun straps the kid on her back and heads out on a frantic journey through the night streets of Seoul to rescue her hubby.

New Korean Cinema:

Take a look back at Korean cinema over the years - from way before the Golden Age right through to the first Korean Wave of the 80s - and you’ll find a steady and almost constant stream of films stressing the importance of the family unit and mirroring the traditional idea that a young woman’s focus should first and foremost be finding a husband, getting married, setting aside whatever her pre-marital life was to take care of her bread-winning husband’s needs and building a home to raise a happy family. In fact, if you were to choose a Korean film at random from the Golden Age of the 60s and 70s, there’s a fair chance you’d find a tale involving the importance of the family unit to Korean stability as a whole and a detailing of any number of perceived threats to the traditional ‘norm’ of family, either as narrative focus or, at the very least, a significant underlying reference.

However, by the time of the New Korean Cinema wave, young Korean adults had begun to embrace a far more modern attitude to life and love than previous generations, with young women especially increasingly asserting their individuality, demanding equality in relationships and seeing success and fulfilment in their own lives as important to their overall happiness with or without marriage. Just as classic Korean cinema reflected traditionalism and the gradual shift to modernity of Korea as a whole (often showing the latter as a danger), New Korean Cinema repeatedly mirrored the ongoing modernising change in attitude, and in the case of Saving My Hubby those references are many in spite of it outwardly appearing to be simply a light-hearted comedy.

From almost the outset, Saving My Hubby positively screams that Geum-sun and Ju-tae got married far too young, with neither having the emotional maturity to cope with the pressures and frustrations of married life and parenthood. While Geum-sun did indeed take the wholly traditional route to marriage (sacrificing her own needs, desires and pursuits completely in favour of marriage and motherhood), she is far from finding the happiness and contentment the traditional ideal implied she would. She almost constantly yearns for the excitement and fulfilment of her pre-marital life as a professional level volleyball player instead of the mundane, housebound existence she currently has and it could even be said that a part of her wishes she’d taken the more modern approach to relationships, either devoting a longer time to her career or not giving it up entirely on being wed.

Certainly, part of Geum-sun’s night-time battle to save Ju-tae is a result of her having little other option as a Korean wife but to try and (traditionally) care for her helpless, hapless hubby but at the same time her efforts are also based on her (more modern female) desire to take control and bring her family unit back to normality.

Ultimately, while classic Korean cinema repeatedly wrapped depictions of family within cautionary tales, detailing actions and events that could or would tear a family unit apart, New Korean Cinema brought an influx of far more upbeat movies such as Saving My Hubby that showed what it takes to hold a family together, and that shift strikes a hugely positive note on the increasing feeling of stability being felt by young adults in Korean society at the time, certainly compared to previous generations.

There was also a trend in New Korean Cinema for the reversal of traditional male/female relationship roles, feisty females paired with weaker, sometimes hapless males that can be seen in a myriad of films from My Sassy Girl to the My Wife is a Gangster series, to My Wife Got Married and beyond... and while at the outset of Saving My Hubby Geum-sun is more manically hysterical than feisty, more neurotic than strong, her overcoming of numerous obstacles on her journey to rescue her hubby and the way in which addresses each of her weaknesses in turn underlines that trend towards depictions of female strength beautifully and says something deeply positive about the changing place of women in Korean society from before and during the time of the New Korean Cinema wave.

Humour:

The humour in Saving My Hubby comes largely as a two pronged attack from trends that have been and are consistently popular in Korean cinema. The first of these could be described as Fish Out of Water comedies, stories of characters taken from their comfort zone and placed in situations utterly alien to them, the often madcap humour coming from their desperate efforts to bring order to chaos while being completely out of their depth. Seen in numerous films from gangsters in a monastery comedy Hi Dharma, to Geum-sun’s Saving My Hubby night-time battle through Korea’s underworld, to Kiss Me, Kill Me’s emotionless hitman falling in love with his target etc etc, these fish out of water scenarios became so prevalent that they sat alongside the equally popular Love Across Time romances, Terminal Illness melodramas, High School horrors and Gangster comedies to almost form sub-genres in their own right.

Of course, Geum-sun is a fish out of water two times over, with both her (initial) inability to cope with married life and motherhood and her seemingly endless, often violent, encounters with a myriad of freaks and reprobates on the streets of Seoul - all with her baby strapped firmly on her back - speaking of (ultimately) female fortitude and resilience at the same time as repeatedly underlining the genuine, often laugh-out-loud, humour that can be so easily derived from fish out of water scenarios.

The other trend that screams from Saving My Hubby is the idea that what can go wrong will go wrong, again seen in a myriad of films from classics such as insurance fraud farce Just Do It, to The Quiet Family’s death upon death at a boarding house, to the far more recent A Hard Day in which a detective desperately attempts to hide a body and cover up the fact that he is responsible for accidentally killing the man. In Saving My Hubby, every step Geum-sun takes pushes her life even closer to collapse and the more she tries to move forward, the more madcap and even hilariously surreal her difficulties become – a classic example of the comic “catalogue of errors” idea that Korean filmmakers have become so adept at detailing . Anyone who has had a day where absolutely everything goes wrong can hardly fail to secretly smile and think to themselves “Thank heavens that’s not me”, even in between the laugh-out-loud moments of Saving My Hubby.

Add to that, the appearance of archetypal characters from multiple genres and references to everything from thriller to Chaser-like action movies ensures Saving My Hubby not only succeeds as a genuinely funny, light-hearted comedy but also shows itself to be as much a reflection of film trends appearing throughout New Korean Cinema.

Bae Doo-na:

I’m sure you’re all aching for the film to start and for me to stop so as a quick final note:

Saving My Hubby stars Bae Doo-na, one of the most internationally recognisable Korean actresses, both as a result of her roles in Park Chan-wook’s masterful Sympathy for Mr Vengeance and the hugely popular and internationally successful Bong Joon-ho film The Host, as well as her appearance in Western films Cloud Atlas, Jupiter Ascending and Netflix sci-fi drama Sense8.

While Bae Doo-na’s Western film performances have tended to be in big budget, blockbuster affairs, her Korean films have often been smaller productions, her choices being based on what the films had to say about the place of women in Korean society, female strength or even societal issues surrounding alternative lifestyles.

I interviewed Bae Doo-na towards the end of last year, and when we talked about those choices she said that while the societal statements made by the films was the most important thing to her, she was aware that as they were often smaller productions they’d likely be seen by fewer people, especially internationally. At that point, I mentioned how much I love Saving My Hubby and Bae Doo-na physically squealed with delight, almost jumping up and down with excitement at the fact that I’d seen one of her much lesser known films (of which she is clearly, deeply proud) and that I’d seen it in the UK. She had pretty much assumed that virtually no-one internationally had watched or been aware of Saving My Hubby and that even in Korea few had seen it.

If Bae Doo-na knew you’re all here tonight to watch this little gem of a movie, I’d virtually guarantee she’d be jumping up and down with excitement all over again.

Enjoy the film.

Hangul Celluloid's 'Singles' Introductory Film Talk at the KCCUK (30 June 2016)

In June 2016, I was asked by the Korean Culural Centre UK to give an introductory film talk prior to the KCCUK 'Korean Film Nights' screening of 'Singles' (2003).

The following is a transcription of that talk:

Trends:

I'm sure most of you have checked out the synopsis of Singles on the KCC's site or wherever. Singles tells the story of the friendship between two women and their various relationships - Nan is nearing her 30s and is pretty sure her life will take the traditional route of decent job and relationship leading to marriage, that is until she's dumped by her boyfriend and demoted at work, while Dong-mi is currently on her 48th boyfriend, is happy to tell anyone and everyone about her rather liberal attitude to life, relationships and sex and has no intention whatsoever of settling down.

The film was released 13 years ago in 2003, but even in 2016 it feels contemporary, wholly modern, to the extent that it could almost stand alongside Korean relationship comedies of the present day. But that fact in itself makes it all too easy see Singles as just another relationship comedy, one in a very long list, and overlook the part it played in huge changes that took place in Korean cinema in the late 90s / early 2000s, a period that's become known as the New Korean Cinema wave.

While the vast majority of discussions about the New Korean Cinema wave can almost be guaranteed to cite Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho etc. as directors whose films fuelled the entire expansion of Korean cinema - using modern filmmaking techniques, merging genres to create highly original films that had an impact both internationally and domestically - far fewer mention the many other New Korean Cinema directors who chose to focus on familiar genres and narrative ideas, bringing a progressiveness to already popular subjects and often imbuing their films with noticeably modern attitudes.

With many of these directors having been schooled abroad, they began to step away somewhat from traditional Korean depictions of relationships, love and romance – such as pre-marital chastity, relationships serving largely as a means to marriage, lasting happiness only coming within the standard ideal of ‘married family’ – and move more towards depictions of relationships as an end in their own right for young adults not yet ready for marital commitment, this more modern attitude coming at a time when young single Korean women were beginning to assert their individuality and become far more sexually aware and worldly wise than previous generations.

In Singles, the character of Nan being dumped by her boyfriend (thereby, in the early stages of the narrative, no longer having a relationship that could lead to marriage), having to learn to be single again, as well as the change in her attitude towards life and relationships as the film progresses can be seen as a mirroring of the gradual move from traditional to modern that that was taking place throughout New Korean Cinema at the time, and indeed in Korean society as a whole.

Of course, stories of sexually aware women pursuing their own needs and desires outside of marriage were certainly nothing new back in 2003, but for decades Korean films had dealt with such subjects as cautionary tales, with such women shown as a threat to traditionalism, family and Korean society as a whole and ultimately punished for their 'wantonness'. In fact, the first ever Korean film where such a sexually voracious woman wasn’t ultimately punished in some form or another for her sexual actions and choices outside marriage was The Adventures of Mrs Park which wasn't released until 1996, just seven years before Singles.

Admittedly, those earlier depictions of independent, modern, sexually aware females looking out for themselves rather than focusing on marriage, husbands and family were much harder and forceful. These women - famously described by Golden Age director Kim Ki-young as "Despicable Women" - were far more conniving, far more self-serving than the fun-loving independent women in films like Singles, but that's kind of the point. New Korean Cinema directors were essentially saying that modern women following their own needs, desires and pleasures was no big deal, it was just life and even something to be celebrated... and that struck a massive chord with female cinema audiences, making films like Singles hugely successful at the Korean box office.

Singles also utilises other popular New Korean Cinema trends, those of depictions of noticeable feisty females and a somewhat reversal of traditional male / female roles – i.e. strong women paired with far meeker, or even hapless, males. There was an absolute explosion in the appearances of these sassy female characters around the time of Singles and slightly before, the most obvious example being Kwak Jae-young's My Sassy Girl in 2001 with its story of a mild-mannered man’s relationship with a hilariously violent, virtually psychotic girl. This switch in gender roles combined with strong female characters was so popular with audiences (especially young women) that a slew of similar examples really had to follow, from the My Wife is a Gangster series of gangster comedy movies to romance Windstruck, to Saving My Hubby - the story of a woman’s fevered journey through Seoul to rescue her husband who has been taken hostage by a bar owner over an unpaid drinks bill, all while carrying her baby on her back. As time passed, the physicality of these sassy depictions mellowed somewhat turning largely to dialogue-based feistiness, resulting in much more realistic and natural narrative humour.

While many of the NKC comedies were aimed directly at those in their pre-marital late teens and early 20s, just as many targeted a slightly older demographic, allowing discussions of modern attitudes to marriage and sex to be included within the humour and speak directly to age groups for whom such issues really mattered. Such is the case in Singles, as well as, for example, The Art of Seduction (telling of a competition between a man and a feisty female to see who is better at seducing members of the opposite sex for a one night stand), A Bizarre Love Triangle (the title really speaks for itself) and, later, My Wife Got Married, in which a strong sassy woman married to a meek man decides she wants to marry a second husband while keeping her current marriage going.

Singles’ use of all of the above ensures that though the film is based on the Japanese novel Christmas at Twenty-nine, it is Korean through and through to the extent that it could almost be considered a poster film for New Korean Cinema comedies.

Humour:

It almost goes without saying that this reversal of traditional gender roles, either overtly or subtly, and the idea of noticeably feisty females easily lend themselves to humorous depictions and director Kwon Chil-in uses them to great comic effect in Singles combining them with genuinely witty dialogue throughout... whether it’s Dong-mi (Uhm Jung-hwa) dragging her trouserless boss across a office by his tie to loudly berate him in front of her work colleagues, or more traditionally feminine Nan (Jang Jin-young) undertaking a sexual liaison dressed as a bunny girl brandishing a whip, while her conquest is on all fours on the floor. This carries through to Nan's thoughts being shown and voiced on screen - on the outside she's shy, polite and respectful - as society would want her to be as a lady - while inside she's the archetypal feisty female, swearing like a trooper and happy to imagine herself beating up a woman in the street on hearing her talk happily about love.

While Singles is wholly modern, Kwon Chil-in nonetheless references a number of cinematic romance and drama clichés throughout, gently parodying them in the process... rain to represent a character's sadness, a 360 degree camera pivoting around two lovers etc etc and in each case Kwon Chil-in has one of the characters point out that it is a movie cliché, almost poking fun at himself in the process.

As a final note on the humour in Singles, there was somewhat of a trend during the New Korean Cinema wave for comedies to use overtly and overly ‘loud’ humour. Take for example Crazy First Love in which actor Cha Tae-hyun’s character spends the entire first half hour of the film yelling almost every line of dialogue at the top of his lungs, getting, as far as I’m concerned, more annoying and less funny with each passing second. Kwon Chil-in wisely avoids such overly contrived attempts at noisy humour in Singles and, by keeping things fairly bright and peppy as well as creating genuinely likeable characters that are easy to warm to, what boisterousness there is comes across as far more legitimate and indeed welcome, succeeding to a much funnier degree.

Jang Jin-young

I’d love to give you an overview of all of the main Singles cast members but time is rather of the essence. So, instead, I’m going to briefly focus on one cast member specifically. That is, actress Jang Jin-young who in her nine film career was nominated for 21 acting awards, winning 14, quickly becoming one of Korea’s best loved actresses, in the process.

Jang Jin-young began her career in front of the camera as a model, and even represented her home province in the 1993 Miss Korea beauty pageant. She briefly moved from modelling to television acting in 1997 and in 1998 she landed her first film role in fantasy drama Ghost in Love. While her tough girl supporting role in Kim Jee-woon’s classic The Foul King in 2000 brought her to the attention of audiences and film critics far more than Ghost in Love, it was her first major starring role in 2001’s Sorum that truly set her on the path to stardom. Telling the story of a chain-smoking victim of domestic abuse who gradually begins to lose her grip on reality, Jang Jin-young’s jaw-dropping performance will at once break your heart and send a chill up your spine... and that performance quite rightly earned her six best new actress awards in Korea and abroad.

In 2003, Jang Jin-young starred, of course, in Singles for which she won another load of awards and Scent of Love – a film about a woman diagnosed with stomach cancer which tapped into New Korean Cinema’s penchant for films dealing with terminal illness. However, following a further two film roles which included the superlative Blue Swallow, a historical biopic about the life of one of Korea’s first women pilots, Jang Jin-young began to suffer from debilitating abdominal pain, and on seeking medical attention was herself diagnosed with stomach cancer, sadly mirroring the narrative of Scent of Love. Life cruelly imitating art, if you will.

She immediately retired from acting and began treatment combining Eastern and Western medicine but though she bravely battled against her disease for almost exactly a year, on September 1st 2009 Jang Jin-young passed away. She was just 35 years old.

During an interview at the time of Singles’ cinema release in 2003, Jang Jin-young said her character in the film had a personality closer to her own than any other role she’d ever played. As such, Singles is a beautifully, genuinely funny comedy that not only stands as a tribute to the talent of one of Korea’s best-loved actresses but also serves as an uplifting reminder of how warm, witty and full of life Jang Jin-young really was.

Enjoy the film.

|

Image copyright: DiyaOnKorea (twitter: @DiyaonKorea) |

'East Winds' symposium (March 2012)

The following paper formed the basis of a talk given by Hangul Celluloid at the 'East Winds' symposium that took place at Coventry University on March 2nd 2012:

‘Sex sells... The emergence and growth of sexual content in Korean cinema’

Introduction:

Within a film industry as historically censored and highly regulated as Korea’s, the emergence and depiction of adult, or sexual, content in Korean cinema has been subject to a slow and rather difficult evolutionary process. Regularly having courted major controversy, graphic adult content (both in terms of narrative and imagery) has nonetheless increased over the years and, as the nature of roles and the balance of power within relationships - as well as the place of women within society - has gradually moved onto a more equal footing, so the nature of adult content has increasingly diversified, largely morphing from simply being a depiction of wanton females out to destroy family life, or women as subservient 'objects', to more often serving as a reference to power struggles within relationships and society as a whole; to empowerment; or even facilitating social commentary on specific historical periods and events, while also directly leading to the eventual emergence of the so called ‘erotic film’, in any one of a number of genres.

In fact, so inextricably linked to, not only censorship, but also government constraints on society at large - not to mention specific Korean current affairs - has sexual content in Korean cinema been over the years, that any discussion of its emergence and growth can largely be seen as a history of Korea itself, and while it would clearly be utterly impossible for me to detail every instance of graphic sexuality that contributed to the eventual growth of adult content in Korean films, certainly within the constraints of a twenty minute talk, this paper will nonetheless attempt to give an overview of some of the most notable cases that together have largely served to shape the attitudes towards depictions of sex and sexuality in Korean cinema seen in Korea today.

Background:

Even as far back as the period that has become known as the Golden Age of Korean cinema - in the late 50's and 60's - sexuality had already begun to be referenced in Korean cinema. Having only escaped from Japanese occupation in 1945 when the Japanese were defeated by Allied forces (Korean films having become little more than a heavily censored outlet for Japanese propaganda during that time), and with the majority of Korean cinema's infrastructure, and even content, having been destroyed or lost during the Korean War, Korea set about rebuilding its film industry with the help of tax incentives and foreign aid, and having spent so long being denied the opportunity to openly promote its individual cultural identity (even Korean language films had been banned by the Japanese in 1942), Korean film output positively exploded - with narratives depicting the classic ideas of morality, purity and the importance of family values (to both individuals and society at large) becoming increasingly commonplace.

Japanese oppression no longer being a current malevolent force and the Korean War having finally come to an uneasy stalemate (even though an official peace treaty was never signed), Korean cinema instead began to focus more of its attention on the perceived threat to the stability of society in the form of subversive elements that could potentially destroy the all-important family unit, and the perfect personification of that threat came in the form of depictions of illicit sex, adultery and sexual betrayal.

The 1960’s:

A clear example of this can be seen in one of the most famous Korean films from the Golden Age, 'The Housemaid' (1960 - Directed by Kim Ki-young), which tells the story of a wanton young woman who installs herself as housemaid to a family to ensnare the happily married man and have him for herself, fully prepared to destroy both his life and his entire family should she fail to get her way.

In spite of there being no nudity or graphically sexual visual imagery in this original version of 'The Housemaid', it positively oozes sexuality and menace throughout, and though the sex within it is implied rather than shown, 'The Housemaid' nonetheless set a benchmark for narrative depictions of sex and the perils of succumbing to base instincts and desires - a benchmark that could really only ever be raised by adding further to the explicitness of representations of sexuality present within narratives and, eventually, visuals.

However, less than a year after the release of 'The Housemaid', General Park Chung-hee instigated a military coup in Korea and, over the next decade, citizens and Korean society as a whole faced ever growing constraints and the curtailing of freedom. It almost goes without saying that the Korean film industry was also severely affected by severe governmental dictates, with increasing censorship over political subject matter and sexual material in films, being placed on films and filmmakers alike.

Nonetheless, some directors managed to find ways to push the boundaries of sexuality and adult content in Korean cinema further during this period, in spite of the almost draconian censorship they faced, and a notable example came in 1968 with Shin Sang-ok's film 'Eunuch'. With scenes of miscarriage, lesbianism, castration and rape within a historical drama set in the Royal Palace, 'Eunuch' brought overt depictions of the sexual act to the very foreground of the silver screen.

Shin Sang-ok would later become known as the director who was abducted under the orders of Kim Jong-il, held captive for years North Korea (following the North’s kidnapping of his wife, actress Choi Eun-hee, in 1978) and forced to make a number of films for the North Korean regime before both finally managed to escape in 1986, but though that fact will always be the headline-grabbing story of his life, his importance in the shaping of adult content in South Korean Cinema cannot in any way be denied.

Once again, the sexual content in 'Eunuch' was presented without the inclusion of full-on nudity (strategically placed ornaments and set props were used to cover the actors' modesty throughout), but the boundaries had been resolutely pushed, nonetheless, to the extent that the subsequent addition of graphic sexual imagery to the mix became almost a foregone conclusion.

The 1970’s

Kim Ki-young stepped up to the plate on that score, in 1972, with 'Insect Woman' which, like 'The Housemaid' dealt with the dangers of succumbing to sexual desires. The film tells the story of a man who checks himself into hospital because of mental issues and there meets several men suffering from schizophrenia as a result of having extra-marital affairs. They proceed to relate the tale of an impotent married man who was killed by his concubine and the film steps back in time to detail not only his affair, which began after he raped her, but also his wife's subsequent discovery of their sexual liaisons and her eventual decision to even pay the girl an allowance for her 'sexual work'. Involved and fairly twisted though 'Insect Woman' is, the main reason I bring it up here is because as well as a deeply sexually charged and altogether groundbreaking narrative, there is also a scene featuring an early example of cinematic visual nudity: As the man and his lover have sex over a glass table, the top of her dress torn aside to reveal her naked breast and, fleeting though that moment is, with it another step along the road to Korean cinema's sexual liberation had resolutely been taken.

As a short aside, the questions of how and why films such as this got past the heavy censorship of the period arises and while the answer is ultimately up for debate, to my mind, the context within which the sexual references and content appeared is likely to have played a part - cautionary tales and morality plays of the perils and pitfalls of illicit sex and adultery (from one perspective, at least) actually served to reinforce the importance of a stable and loving family to ultimate happiness and even wellbeing, and, in fact, it wouldn't be until many years later, in 1996, that The Adventures of Mrs Park (directed by Kim Tae-gyun) would finally become the first Korean film to show a positive ending to an adulterous liaison.

Insect woman was another Kim Ki-young film that came just before a further governmental censorship clampdown. In 1973 changes to the Motion Picture Law were made stipulating that all films were required to reflect the so-called 'Revitalising Government', and this, in one fell swoop, heralded an altogether bleak and barren period as far as worthy South Korean films were concerned, save for a number of 'hostess' films detailing tales of lower class women driven into prostitution.

Not only did controversial storylines and adult content dwindle to almost non-existence, but the Korean film industry quickly regressed to (once more) being little more than an outlet for government propaganda and, being one of only a very few 'safe' genres of film allowed by the state, melodrama became largely predominant - still being hugely prevalent, to this very day. It'll likely come as no surprise to learn that Korean cinema audience numbers plummeted as a result and it wasn't until a new president and government came to power in the latter part of the 1970's that the situation had any hope whatsoever of changing.

The 1980’s

Those changes, when they finally began to take place in the early 80's, saw a relaxation of attitudes towards, and censorship of, sexual material in film, and like anything natural that is forcibly repressed and subsequently somewhat let loose, adult content; sexual narratives and imagery quickly began to appear - and with increasing frequency.

While some filmmakers were content to use adult content and imagery as a visual representation of voyeurism, lust and/or oppression (such as Koo Young-nam's 1981 horror film 'Suddenly at Midnight', in which a coveted woman is repeatedly shown with voyeuristic camerawork - filming her in the bath, having the camera repeatedly focus on various parts of her anatomy and even showing a number of what can only be described as up-shirt shots), some directors had altogether far more to say and used their new-found freedom to express sexuality in their films to make social commentary on the changing face of Korean society itself.

One of the most famous examples of this (well, famous to me at least) can be seen in 1984 film 'Between the Knees'(Chang-Ho Lee): After the Gwang-ju uprising of 1980, Korea slowly began to step tentatively towards social reform (leading to a new constitution in 1988 and eventual democracy) and with the younger generation in the 80's being increasingly influenced by the West and Western ideals (having far more access to the outside world than their parents ever did, via foreign cinema output etc.), young women, especially, were becoming far less willing to accept similar lives to those of the older generation - getting married at the first opportunity and giving themselves and their desires over entirely to their husbands and families - and they understandably felt well within their rights to demand the lives that they really wanted, lives they could see others living - with equality, a career, love and, of course, sex. 'Between the Knees' details this social battle, if you will, in its story of a young woman so at odds with the wishes of her puritanical mother that she can't manage to focus on anything, save thoughts of the sex she so desires, both for pleasure and to rebel against her family, all wrapped up in a tale of knee-focused sexual imagery.

The 80's also saw the release of Korea's first erotic sex film in 1982: 'Madame Aema' (directed by Jeon In-yeop) told the story of a woman who engaged in a series of extra-marital affairs while her husband was in prison, and was by far the most sexually explicit film made in Korea up until that point, spawning a number of sequels. It's likely that the box office success of an erotic film like 'Madame Aema' indirectly led to the making of Lee Doo-yong's 'Mulberry' in 1986 - another erotic tale (based on a famous story by Na Do-hwang) that tells the story of a beautiful woman (during the Japanese occupation) who spends the long periods gathering mulberry leaves and having sex with the majority of the men in her village while her husband's away from home, all the while trying to break free from the shackles of her life - the theme of a woman trying to exert her independence and individuality while desperately trying to escape her authoritarian (and implied sexually inadequate) husband and family life yet again speaking of the slowly changing place, wants and needs of women in society.

The 1990’s

The new constitution of 1988, democratic reforms and further relaxation of censorship laws combined with outside investment from businesses and industry to give the Korean film industry a boost in the 90's, and the more adult content that appeared, the more directors inevitably tried to push the boundaries of its explicitness; the more relaxed they felt about the use of sexual storylines combined with graphic imagery, the more they strived to find ever increasingly controversial situations in which to depict it. Regardless of the fact that the censors were being far less constrictive than they once were, there was clearly bound to come a time when a film would finally cross the line of what was deemed morally acceptable.

That time came when 'Yellow Hair' (directed by Kim Yoo-min) was put before censors prior to its intended release. The Korean Media Ratings Board rejected 'Yellow Hair' outright, tantamount to banning the film - describing it as having "scenes which are disgusting and totally unacceptable to our moral standards" - and an eventual release was only granted months later after certain scenes had been cut and the graphic imagery in more than one scene had been darkened and blurred.

'Yellow Hair' was the first film to ever be rejected by the Media Ratings Board and its treatment served to set a rather dangerous precedent, almost guaranteeing that other future films would meet the same fate.

The next incident of a film feeling the wrath of the Media Ratings Board came, unsurprisingly, sooner rather than later. Just a year after 'Yellow Hair', 'Lies' (the story of two lovers with a large age gap who get lost in a world of love motels and masochism, directed by Jang Sun-woo) was rejected not once but twice, the two rejections coming two months apart. Finally on the third attempt, after several cuts were made to scenes and explicit language, 'Lies' received an 18+ certificate in 2000.

However, considering the fact that 'Happy End' (directed by Jeong Ji-woo) was released with an 18+ certificate in the same year as 'Yellow Hair' and contains sexual content and graphic imagery every bit as explicit as either it or 'Lies', it becomes increasingly clear that the problem the Media Ratings Board had with both films it rejected was down to the context in which the sex and nudity appeared.

Both 'Yellow Here's and 'Lies' focused on characters on the outskirts of society and, for the majority of each film, they survived and rather enjoyed life perfectly well by doing so while 'Happy End' centred around adultery and betrayal within an outwardly normal(ish) family unit, speaks volumes and the scene in 'Yellow Hair' that received the most brutal cutting by the censors being one showing a sexual threesome between the two main female characters and their male lover adds further proof to this, if more proof were needed.

That, to my mind, clearly infers that even though society, the nature of relationships and the balance of power within them was changing, it would take the powers that be a lot longer to come to terms with alternative lifestyles.

2000 and Beyond

A year after 'Lies' was finally released, the Media Ratings Board once again chose to reject a film, 'Yellow Flower' (directed by Ji-sang Lee), but as a result of the film's distributor bringing an action against the censor, the Constitutional Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to refuse a film a rating and barred the Board from completely rejecting any cinema releases from that point on.

A true step forward for the film industry, democracy and free speech, if ever there was one.

In the subsequent years to the present day, governmental constraints affecting the Korean film industry have obviously become far less of an issue, and while censorship still rears its ugly head from time to time, it causes nowhere near the number of issues it once did.

However, as adult content in Korean cinema becomes ever more explicit, the question of where the line between art and pornography lays (if it even exists) becomes increasingly difficult to answer. On the one hand, directors who consider themselves as serious filmmakers will often claim that adult content in their films is used as a dissection of society; a critique of hypocrisy contained within moral ideas and social norms; or even as historical allegory; while on the other, you can almost guarantee detractors will allege that they considered the overall picture in coming to their conclusion on the worthiness of specific cinematic sexual content and imagery.

How much specific content is, in reality, simply used as expensive wrapping around titillation and sexual gratification is, of course, less discussed, but strip away all the rhetoric and hyperbole given by either side in the discussion and you're left with one very simple question: Is sex still a dirty word?

Whether or not you allow your opinion on the depiction of sex in a particular film to be influenced by others, and ultimately whether you believe that governments and censors should have the right to dictate what a society should, or shouldn't, be allowed to see, will likely be reflected in how you feel about adult content in films in general but, either way, the very least that these films deserve is to be judged on their individual merits - viewers making up their own minds on a case-by-case basis, without being clouded by pre-conceptions, hearsay and assumptions.

Finally, before I run over time and get physically dragged off the stage, a few recommendations of Korean films containing adult content that you really should see, if you haven't already:

Historical:

Portrait of a Beauty and Untold Scandal: both detailing an outwardly moral historical society bubbling over with a far more salubrious underbelly, and asking what happens to true, pure love when it's brought into direct conflict with it.

And...

The Servant - billed as an erotic rom-com, The Servant is a film with less depth than either Untold Scandal or Portrait of a Beauty but is worthy of your attention, all the same.

Contemporary:

A Good Lawyer's Wife and Green Chair: Love and sex within affairs frowned on by society, both featuring relationships between older women and younger men.

The Scarlett Letter: Forbidden love and longing within forbidden love and longing all wrapped up in a murder/mystery thriller.

Summertime: A brutal and highly sexually charged dissection of love, power, adultery and betrayal serving as a metaphor for the Gwang-ju uprising in 1980.

The Housemaid: A sexually explicit reworking of Kim Ki-youn’s 1960 original detailing class structure and struggles in Korean society.

...and one to avoid:

Natalie: Korean's first 3D film, Natalie attempts to bring 3 dimensions to depictions of love sex and erotica but fails miserably on every count. Badly done 3D effects (certainly the red/green 3D found on the Korean DVD) and a, frankly, dull story that lurches into forced, utterly false, and while we're at it, unbelievable melodrama.

'Asian Exposure' symposium (March 2011)

The following paper formed the basis of a talk given by Hangul Celluloid at the CUEAFS 'Asian Exposure: East Asian Cinema in a Global Context' symposium that took place at Coventry University in March 2011:

'Love, Loss and Laughter in Korean Cinema'

Introduction

In every life, there are instances and periods of love, loss and laughter. In fact, those instances are a large part of what actually constitutes living, as opposed to just existing - across all races, all cultures and all religions. In Korean cinema too, ideas of love, loss and laughter not only regularly appear, but are also often essential elements in a plethora of genres and the film storylines contained within them. Not only that, but love, loss and laughter regularly occur side by side within single Korean films, often referencing and commenting on social, political and historical events and ideals along the way.

Emergence of Melodrama Predominance

With the Korean film industry historically having been subject to heavy government constraints and censorship, genres with subject matter deemed as non-provocative (politically or otherwise) gradually became mainstays of South Korean cinema and, of these, melodrama was easily the most prevalent. In fact, melodrama has become so ingrained in the national cinema psyche that as cinematic censorship and constraints have gradually eased over the years, it has remained, and continues to be, an integral part of Korean cinema to this very day.

It virtually goes without saying that romance and tears were, and are, inherent to melodramas - providing two of our love, loss and laughter trilogy, almost ready made -

and with the genre having become so familiar to Korean audiences over the years, the addition of elements of melodrama to other separate genres was almost guaranteed to both occur and subsequently become commonplace.

Genre Focus

Obviously, an in depth dissection of every genre in which love, loss and laughter appear would be utterly impossible within the given time frame of this talk, and would require me to stand here talking for days, possibly weeks. So, for the purposes of this overview, I’ve chosen to concentrate on one specific genre in depth, but will also give several notable examples of love, loss and laughter appearing together in single films from various other genres, towards the end of this paper.

The genre I have chosen to focus on specifically is romantic comedy, which, like melodrama, contains two of the three elements of love, loss and laughter, by its very definition and, more than any other genre, regularly combines romantic, comedic and heart-wrenching ideas to meld that love, loss and laughter together in one place.

So, as is the case with the majority of films referenced throughout this discussion, before we reach the loss and its underlying commentaries, let’s deal with the love and the laughter:

Worthiness

It is only fairly recently that romantic comedies have been deemed as worthy, or "proper", cinema, thanks in part to the influx of new, younger filmmakers, with fresh and innovative ideas, forming part of the emergence of what has been deemed ‘Korean New Cinema’. Having grown up with access to film content from around the world, and with many schooled in film studies in the West, these new auteurs made a point of subverting social stereotypes and familiar storylines within films to bring a revitalising freshness and plot innovation to virtually every genre, not least romantic comedy.

My Sassy Girl

The biggest change in perception of the genre occurred in 2001 with the release of My Sassy Girl (Kwak Jae-yong) - a film which would subsequently have a huge effect on not only the romantic comedy genre, but also on a plethora of associated sub-genres. Based on the real life internet blogs of Kim Ho-sik, detailing his relationship with his girlfriend (which had a huge following among female teens and those in their early twenties), the film was targeted specifically at the blog's fan base and gave this audience demographic a subject matter which they could both relate to, and in which they were actually interested. A complete reversal of the stereotypical male and female roles within Korean society can be seen in My Sassy Girl - a feisty, aggressive and bullying (unnamed) female (played by Jun Ji-hyun), in a tumultuous relationship with a rather passive "mummy's boy" male, Kyun-woo (played by Cha Tae-hyun), with the majority of the laugh-out-loud humour being based around this inversion of the usual male/female roles, the resultant sassy actions of "The Girl", as well as others' reactions to her behaviour - and this further resonated with the younger generation of cinema goers, who were beginning to develop different attitudes regarding the place of women within society.

Windstruck

Thus began a trend for romantic comedies featuring forthright female characters holding the power and control within their loving relationships with weaker males, such as Windstruck (2003 - Kwak Jae-yong), in which a "sassy" policewoman begins a romance with a quiet, unassuming man, whom she mistakenly arrests. However, within the humour found in this subversion of male and female places within relationships, an underlying, almost virginal, purity to the main female characters is also noticeably prevalent, due, in part, to Korean society's long held attitude that sex before marriage, and even overt public displays of affection, were unseemly. Thus the love element of our love, loss and laughter trilogy largely takes the form of pure, almost innocent, romance.

Innocence

For example, the characters in neither My Sassy Girl nor Windstruck ever even so much as kiss: In Windstruck, when Myeong-wu (Jang Hyuk) attempts to kiss Gyeong-jin (Jun Ji-hyun) she, instead, makes him close his eyes and burns his lip with a red-hot stick which has been lying in a fire - the underlying implication of the importance of female pre-sexual innocence and chastity repeatedly seeking to reinforce the belief that a woman being chaste and pure at heart was an ideal to be sought after and followed, and that doing so would eventually lead to a happy life within a stable, loving family.

Crazy First Love

This carried through to films such as Crazy First Love (2003 - Oh Jong-rok), in which the main male character, Tae-il (Cha Tae-hyun), makes a pact with the father of the girl he wants to marry, Il-mae (Son Ye-jin), with the comedy present largely resulting from his efforts to keep her chaste and virginal until he has finished his studies, thus becoming an upstanding member of society worthy of asking for her hand in marriage, and at the same time ensuring that she remains worthy of being sought.

My Wife Got Married

More recently, the noticeable change in attitudes to what constitutes family (and what is considered as acceptable, sexually, within relationships) is apparent in films such as My Wife Got Married (2008 - Chong Yun-su), in which monogamy and polygamy are discussed, compared and contrasted. The film also carries on the aforementioned trend of humour resulting from the characterisation of a strong woman, (In-a, played by Son Ye-jin), who has the dominant, powerful role in a loving relationship with a passive (and, in this case, a rather neurotic) male, (Deok-hyun, played by Kim Joo-hyuck), and builds its tale around the love and laughter between the two. My Wife Got Married also boldly adds the addendum that, though love, happiness and stability can indeed be found in marriage, it does not necessarily have to be within the Choseun ideal of family - where a woman was very much seen as a subservient individual, expected to sacrifice her own needs for those of her husband and children, above all else. However, even though both adultery and the differing attitudes to sex and relationships of the youth of today from those of older generations, are discussed in My Wife Got Married, there remains an inference, which is also present at the core of all of the aforementioned films, that marriage and commitment are still the ultimate female character/relationship goals.

Loss

And so, with the love and laughter elements firmly in place, providing commentary on the social norms, morals and etiquette of South Korean society, it’s time to bring some loss into proceedings:

As already stated, the melodramatic ideas of yearning, separation, heartbreak and loss present in any romance or relationship easily allow melodrama to take its place as an integral part of the South Korean romantic comedy genre, but that really is just the tip of the iceberg. In a country which has been subject to as much political, social and economic turbulence and upheaval as Korea has, references to these ideas almost cannot help but appear in virtually every film genre, and within romantic comedy tales, events in the lives of characters often appear as veiled analogies to Korea's tumultuous history.

With regard to My Sassy Girl, the main, unnamed, female character is gradually shown to have a past full of heartache, loss and separation from an earlier love, and comparisons cannot fail to be made to South Korea's split from being a single unified country and the impassable separation brought in following the Korean War, in the form of the DMZ. The Girl's obsession with time travel and dreams of being transported to either the future or the past in order to save the person she cares for also echo the country's desire to put its painful past to rest and move to a time of security and stability, regaining happiness and eradicating animosity in the process. Windstruck too, makes references of a similar nature by having the main characters eventually separated and kept apart by, seemingly, insurmountable barriers and, once again, a mirroring of the continuing separation of North and South Korea is clearly on show.

Specific Historical references – A Man Who Was Superman

However, there are also instances where the references within film narratives are much more overt and historically specific, actually forming a major part of the plot.

One such example is A Man Who Was Superman (2008 - Chung Yoon-chul), which tells the story of jaded human interest documentary maker, Soo-jung (Jun Ji-hyun), who endeavours to make a television programme about a man who claims to be Superman, (played by Hwang Jung-min), and gradually forms an increasingly close bond with him in the process. A Man Who Was Superman utilises the real-life events of the 1980 Gwang-ju uprising (during which more than one hundred civilians were killed, and many more injured) as a pivotal element of its plot and as the story of Superman’s past is gradually brought to light, it’s clearly shown that, though the events which happened to him at Gwang-ju caused his problems in the first place, his resultant medical issues have also allowed him to forget, not only the traumatic event itself, but also the heartbreak and loss suffered by him in the subsequent years, thus allowing him to be happy, and giving him a love of humanity and a desire to help those in need. Once his memories are restored, he utterly falls apart, becoming a shadow of his former self, and the narrative’s underlying intimation that Korea is still coming to terms with its historical struggles, and that only by putting the pain of the past behind it, forgetting historical animosities, and concentrating on the present and future, can it find permanent happiness, contentment and stability, is impossible to deny.

Sexual Content

Over time, as sexual content has become somewhat more accepted in South Korean cinema, a gradual increase in the graphic nature of sexual references and imagery within even mainstream films has been seen, and these too regularly combine the ideas of love, loss and laughter to tell engaging tales within whatever social or historical setting their stories require . As recently as 2010, The Servant (Kim Dae-woo) combines a romance based on the Korean folk tale The Tale of Chun-hyang, with sexually based humour and Category III level visuals and content, to create what can only be described as an “erotic rom-com” but, even here, references to the characters’ past difficulties and ongoing social constraints are in evidence and, with a melodramatic coda being added to the humour and romance present, once again, the trilogy of love, loss and laughter is complete.

Lead-out

Of course, not every romantic comedy will contain references, veiled or otherwise, to Korea's turbulent history, with films such as the aforementioned My Wife Got Married largely focusing on present day social commentary and presenting the element of loss simply as that caused by the day to day events within on/off relationships, and not all will even include all three of the elements of love, loss and laughter, but their combination in films has become so familiar to audiences and filmmakers alike that a template for a large section of the genre has virtually been created.

Summation

The summation of this discussion on love, loss and laughter will likely come as no surprise whatsoever to anyone here: Like so many Korean romantic comedy characters, Korea too has had a past full of turmoil and loss, has been split and separated, with seemingly impassable barriers put in its path, and is ultimately still trying to smile through the pain, while attempting to ensure that its present becomes a happy, stable future, filled with laughter and love.

As the final piece of this paper, I would like to give just a few short examples of notable films from various other genres which also feature the combination of the three elements of love, loss and laughter.

Other Genre Examples

Joint Security Area (2000 Directed by Park Chan-wook)

Set at the DMZ separating North and South Korea, Joint Security Area details an investigation into a South Korean soldier found stumbling across no man’s land with two North Korean soldiers having been left dead, in his wake.

Love & Loss